Rime (stylized as RiME) is an atmospheric 3D exploration adventure game released in May 2017. Its aesthetics are heavily influenced by The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, while its nonviolent gameplay is a tribute to Journey. You’d think this game would be made specifically for me, but I didn’t like it. The music and graphics are beautiful, but the gameplay is abysmal, while the larger story is almost laughably trite. What I’d like to do is try to explain why Rime didn’t work for me.

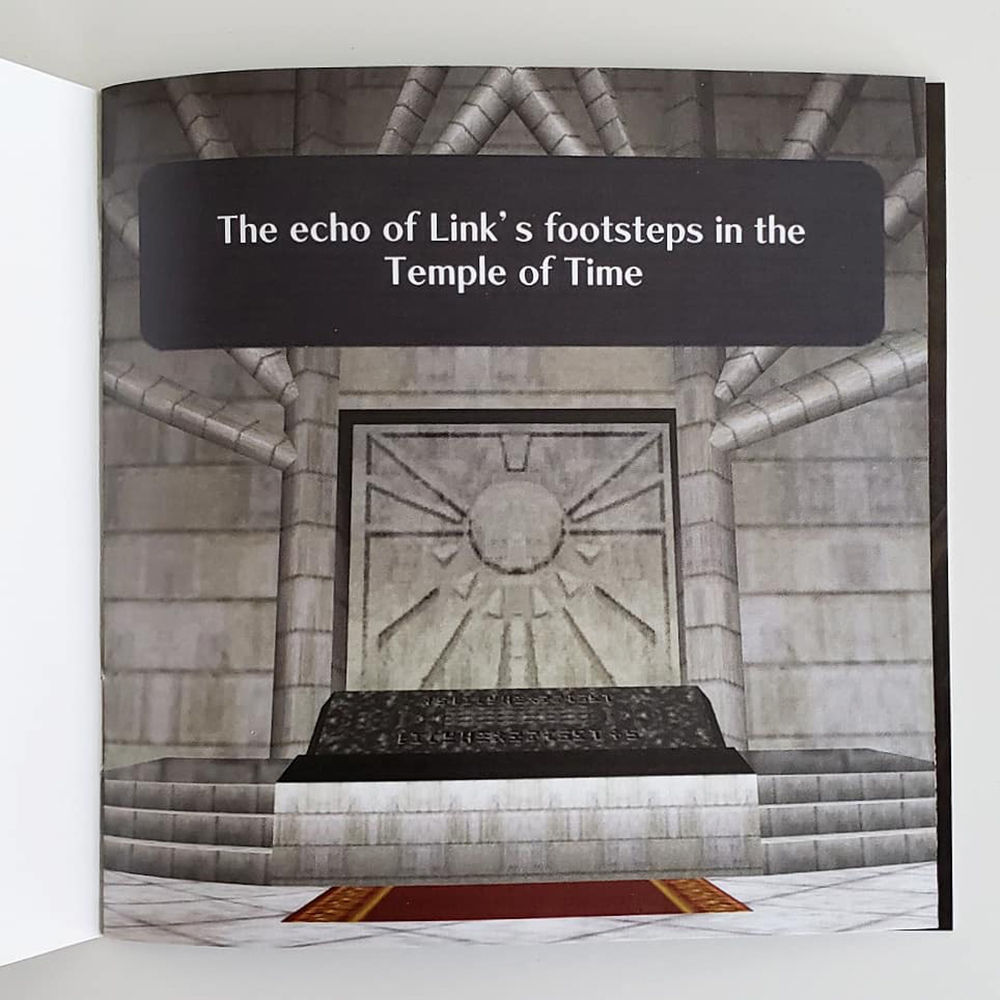

Like Journey, Rime doesn’t tell the player how things work but instead helps you figure out the mechanics for yourself through environmental design. At the beginning of the game, a young boy washes up on a deserted island, and within the first few minutes he’s given the task of activating four statues. Each of these statues is marked by a bright blue beam that serves as an obvious goalpost indicator. One statue is just off the main path from the beach to the interior of the island, one requires the boy to feed fruit to a boar so that it will move out of his way, and one requires the boy to dive and swim through an underwater passage in order to reach a small offshore structure.

Rime gently guides the player through the actions needed to achieve the first of these three goals. When the boy stands next to the first statue, the triangle button appears onscreen, showing the player how to activate it with the “voice” command. When the boy stands close to the fruit bushes next to the second statue, the square button appears onscreen, showing the player how to pick the fruit with the “interact” command. When the boy swims to the small structure in the bay, the cross button appears onscreen, showing the player how to dive using a variation on the “jump” command. No problems here.

The difficulty with the fourth statue is that it’s far away from the point of specialist action needed to reach it. Moreover, this target point is not flagged in any way. What the player is supposed to do is use the circle button (which otherwise makes the boy perform a somersault) to drop down from a cliff so that the boy hangs from it by his fingertips. He then shimmies along its edge until he can jump to another cliff before following a path to the other side of the island.

There are plenty of cliffs on the island, but most players will have learned that they mark boundaries, as jumping off of them will result in death. Climbable ledges are marked by white erosion patterns, but the player can’t see these patterns from above. Since the cliff the boy needs to navigate is so far away from the actual statue, it would stand to reason that the circle button would appear onscreen when the player approaches this particular cliff – but it doesn’t.

I therefore spent a good 45 minutes running around and trying to jump over or climb up or somersault through piles of rocks close to the fourth statue, all to no avail. I finally had to give up and resort to a video walkthrough. This sort of failure in accessible design wouldn’t be a flaw in a game that’s meant to be difficult, perhaps. Unfortunately, it’s definitely a problem in Rime, which consistently feels twitchy and stressful instead of expansive and atmospheric.

Where Rime succeeds are its striking and brightly colored landscapes, but the game forces the player to spend an inordinate amount of time in unlit interiors fooling around with finicky moving block puzzles hindered by awkward camera angles. On top of that, Rime‘s platforming elements are atrocious. The boy’s jumps won’t successfully land unless he’s positioned in exactly the right place and at exactly the right angle. Again, the camera angle often doesn’t help. The character moves so slowly that returning to the jump point is often a tedious process, especially later in the game when chains of jumps must be completed.

The narrative payoff for the platforming and block puzzles is that the player gradually learns the boy’s story. I suspected that, like other indie games in which a child must complete trials in an otherwise empty world, the boy might already be dead. If that was the case, I wasn’t sure that the emotional payoff of the game would be worth the frustration.

It turns out that the boy is in fact dead, having fallen overboard during a storm while on a boat with his father. It’s not clear whether you play as the kid’s soul making the transition from life to death or whether you play as the father imagining the kid’s fantasy adventures as he navigates his grief, but the last bit of the game involves the father walking around the kid’s room and picking up the kid’s toys, each of which played a symbolic role in the game (a stuffed fox is the fox spirit that leads you through the early stages, and so on). I am predisposed to cry at video games, but this revelation came so totally out of left field that I had no reaction at all.

I think I would have preferred a more straightforward story of a kid being shipwrecked on an island and discovering the remains of an ancient civilization. The game is structured so that the boy is able to visit the island in what seems to be different time periods. In one era, it’s lush and green. In another, it’s filled with ghosts and sand-choked ruins. In yet another, there are robots. Many of the game’s puzzles involve circles, orbits, the sun and moon, light and darkness, and other elements that suggest the cyclical nature of time. It would therefore make sense, both in terms of game design and gameplay, to have the game’s theme be the ultimate ephemerality of human achievement within the endless flow of time.

I can imagine a number of interesting endings in line with this theme. It would be cool if the boy gradually realized that he’s the heir to this ancient civilization but then left everything behind on the island so that he can go home, for instance. Or perhaps the boy might inadvertently (or deliberately) destroy everything on the island, but this wouldn’t be a tragedy to him. Or maybe the boy was sent to the island as some sort of trial or pilgrimage in order to become an adult.

At first glance, Rime seems to have a lot of potential, but I was disappointed that it isn’t more thematically cohesive. As it stands, the game feels like a waste of what could have been a gorgeous work of environmental storytelling. I’m not sure that even the most resonant of themes or the most brilliant storytelling could make up for Rime’s endless series of needlessly frustrating puzzles and godawful platforming, though. In the end, all the art and atmosphere in the world can’t compensate for a poorly-designed game that feels bad to play.

Still, I don’t have it in my heart to say that there’s nothing good or interesting about Rime. It’s not a long game, maybe only about seven or eight hours, and parts of it are genuinely beautiful and clever, especially toward the beginning. Since there’s no payoff at the end, my recommendation would be to get Rime when it’s on sale and enjoy it until it stops being fun.