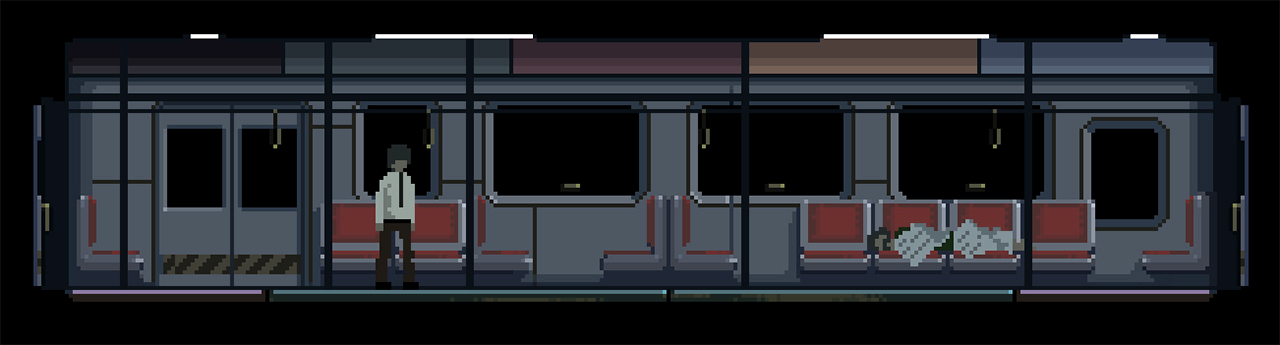

Oxenfree is a horror-themed teenage friendship drama conversation simulator set on a haunted island in the Pacific Northwest. Originally released in 2016, Oxenfree is available on all consoles, and it takes about four and a half hours to finish the story.

You play as a teenage girl named Alex who takes the last ferry out to Edwards Island with her pothead friend Ren and her edgy stepbrother Jonas. They plan to spend the night on the beach, where two girls named Clarissa and Nona are waiting for them with a cooler of beer. There’s an urban legend that old-fashioned transistor radios can pick up strange signals on the island, and Ren leads Alex and Jonas to a sea cave where the signal distortions are rumored to be strong. By tuning into the radio transmissions, Alex ends up opening a portal to a parallel dimension.

I really enjoyed Oxenfree, both when I first played it and when I revisited it earlier this year. The graphic design is gorgeous, the OST is ambient and chill, and the elements of horror are genuinely creepy. The story of Oxenfree is intriguing, and walking across the island while navigating Alex’s relationships with the other characters is a fun and interesting experience.

Still, as a game, Oxenfree suffers from two major problems.

The first of these problems is that Alex walks very slowly. This makes sense, as a major element of gameplay is choosing Alex’s response in real time during ongoing conversations. The relaxed speed of travel also encourages the player to enjoy the scenery and the ambiance. Unfortunately, backtracking is a slog. The frustration engendered by Alex’s sluggish walking speed is exacerbated by the fact that the load times between screens are obscene, usually exceeding sixty seconds. As a result, I felt strongly discouraged against unguided exploration.

In order to uncover the full story of what’s happening, the player needs to embark on a scavenger hunt to collect a dozen letters scattered across the island. Because of the slow character movement and unbearable loading times, I had to give up on finding the letters myself. I was reduced to searching for spoilers online, which isn’t ideal.

As far as I can tell, a Cold War era submarine somehow managed to get itself caught in a dimensional paradox just offshore, and the Edward Island’s “ghosts” are the manifestations of the sailors trying to free themselves. These ghosts are secondary to the main story of Oxenfree, which is about the relationships between the teenage characters.

Although I think the friendship drama might have been more compelling if I had encountered the game at a younger age, Oxenfree’s second major problem is that its writing feels strange and awkward, at least to me.

I really wanted Alex to spend time with the two other teenage girls on the island. I like Nona and Clarissa a lot. I found them to be interesting characters, and I wanted to know more about them. Unfortunately, Oxenfree doesn’t give Alex many dialogue options to interact with either girl that aren’t petty, condescending, or downright bitchy. This isn’t the way that normal people talk to one another, even if they’re teenagers.

It’s clear that Oxenfree expects Alex to spend the majority of its playtime with Jonas and Ren, both of whom tend to respond poorly if the player chooses conversation options that don’t read as stereotypically “masculine.”

To give an example, after something terrible and upsetting happens, Jonas tells Alex that he’s scared. If she demonstrates sympathy or empathy by responding with “Are you okay?” or “I’m scared too,” Jonas will become annoyed or openly hostile. Meanwhile, the uncomfortably callous response of “You’re fine, let’s keep going” is configured as “correct” and doesn’t result in a string of passive-aggressive insults.

There are several different variations on Alex’s personality that the player can choose to express, but Oxenfree doesn’t give the player many opportunities to be chill, or friendly, or sincere, or emotionally vulnerable, or just curious about what’s going on. Each conversation choice generally has three options, but there’s always an additional option of not saying anything. As I played, I gradually found myself “choosing” not to say anything, especially not to the boys.

In other words, the opportunities for roleplaying the character of Alex are limited. I don’t think Alex is supposed to be unsympathetic, but the writer/director’s understanding of how interpersonal communication works feels very specific to a personality and worldview that I don’t understand. The portrayal of these teenagers – especially the teenage girls – is just so mean. The voice actors all give wonderful performances that help the player better understand the characters, but I wish the writing were as nuanced as the acting.

Granted, Alex ends up being the villain of Oxenfree II, so another interpretation might be that she is in fact a bad and selfish person who doesn’t care if she hurts people. If this is indeed the case, though, I wish that the writing had signposted her personality more clearly, or at least given more concrete hints regarding how the true nature of the situation on Edwards Island has affected her character.

Oxenfree has been universally praised, and I’ve even seen people refer to it as a “cozy game,” meaning that it presumably creates a sense of warmth in the player by being unchallenging to play while focusing on a story with themes of friendship and personal growth. I can understand the affective positivity of this reaction, but I also think it’s important to explain why Oxenfree can be difficult and frustrating, especially to someone playing the game in 2024.

Oxenfree is gorgeous to look at and features engaging conversation-based gameplay mechanics, but this is a horror game with slow movement speed and long loading times in which characters are often seriously unpleasant to one another. I maintain that Oxenfree is a unique and interesting game that’s well worth checking out – especially given its relatively short length – but it’s always good to have an accurate understanding of what you’re getting into.

While doing some research about the game’s reception, I learned that Netflix acquired the Oxenfree development team, Night School Studio, in 2021. Netflix produced Oxenfree II, and I read that there’s a live-action series adaptation of Oxenfree in production. This sounds nice, to be honest. Crossmedia adaptations don’t always succeed, but I get the impression that Oxenfree might actually work much better if it weren’t an interactive video game.