Mr. Saitou is an Undertale-style narrative adventure game (with music by Toby Fox) that takes about two hours to finish. You play as Saitou, a white-collar worker who finds himself in the hospital after a failed suicide attempt triggered by stress and overwork. While sleeping, Saitou dreams of himself as a llamaworm (a comically extended groundhog) who goes on an adventure with a cute pink flowerbud named Brandon, the dream persona of a young child Saitou meets in the hospital.

Mr. Saitou has something of slow start, during which the player’s sole job is mashing a button to advance text. Thankfully, the game becomes much more engaging after the first ten minutes, at which point Saitou enters the dream world.

After the introduction, Saitou spends about half an hour in an office of llamaworms that serves as a stage for a gentle comedy about workplace culture. After a ten-minute segment of mandatory afterwork socialization in an izakaya, Saitou returns home to his neighborhood of underground tunnels.

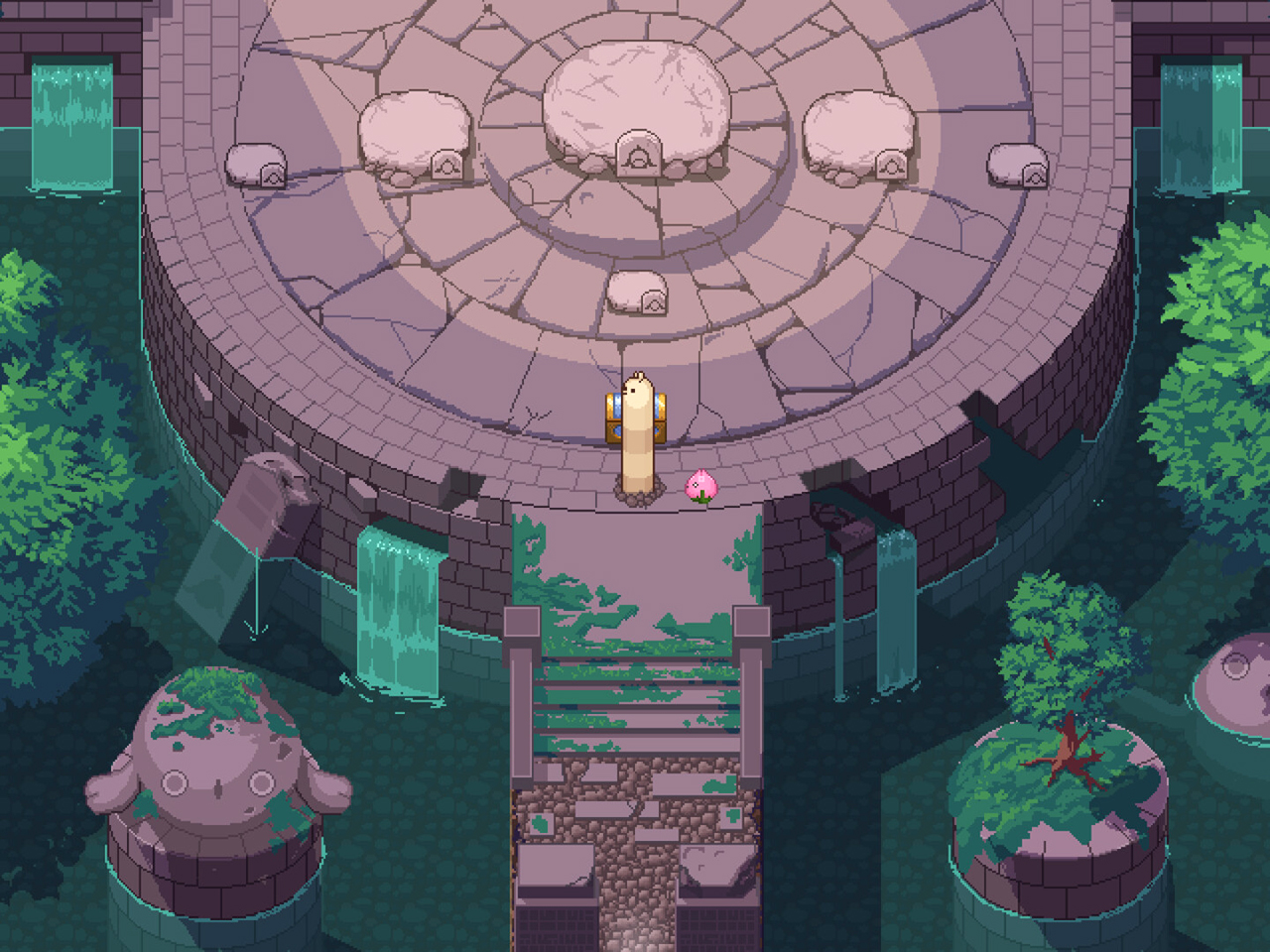

Saitou decides to skip work the next day. This gives him an opportunity to meet Bradon, who wants to visit the Flooded Gem Caverns deeper in the tunnels. The remainder of Mr. Saitou unfolds in a beautiful fantasy-themed underground space enhanced by lowkey elements of exploration and simple puzzles.

What I appreciate most about Mr. Saitou is its creativity, which is driven by cute but thoroughly original character designs and clever writing. Even though most of the gameplay consists of simple conversation-based fetch quests, I never got tired of seeing what was around the next corner, and I always enjoyed talking with each new character.

The game’s humor sits comfortably at the intersection between wholesome and quirky, and the writing subtly references internet culture without relying too heavily on these allusions. The simple spatial puzzles are easy and engaging without feeling as if they were phoned in, and the thematic background music is lovely from start to finish.

I love almost everything about Mr. Saitou, but I should probably mention that there’s an unskippable musical cutscene featuring about three minutes of unremittingly flashing strobe lights toward the end. If you (like me) are photosensitive, this may be worth taking into consideration.

In addition, the sentimentality of the ending may ring hollow for players searching for a more nuanced or complicated story, especially regarding the extent of an individual’s personal responsibility for ensuring their quality of life under late-stage capitalism. This is a valid criticism, of course, but Mr. Saitou is a game about a llamaworm and a talking flower having magical underground adventures. All things considered, I think it’s probably best to enjoy the game for what it is.

Mr. Saitou is a sweet but still surprising game that’s entertaining to read and engaging to play, and I feel that its story earns the right to state its final message clearly: The world is filled with interesting people and beautiful places, and there’s more to life than slowly killing yourself for your job. Good health is a blessing, so you might as well make the most of your time on this earth while you’re still young.