Beacon Pines is an isometric narrative adventure game that takes about four hours to finish. You play as a 12yo boy named Luka who decides to explore a mysterious abandoned factory over summer break and accidentally uncovers the dark secret of his quiet mountain town in the process.

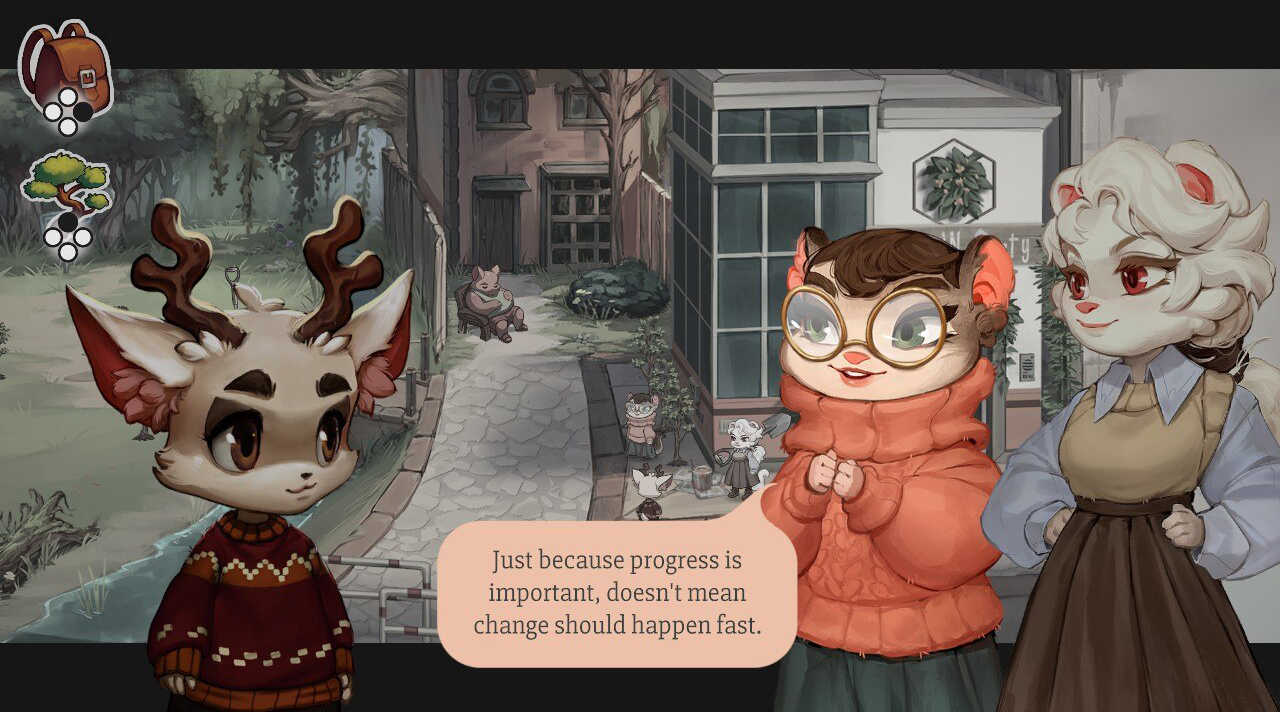

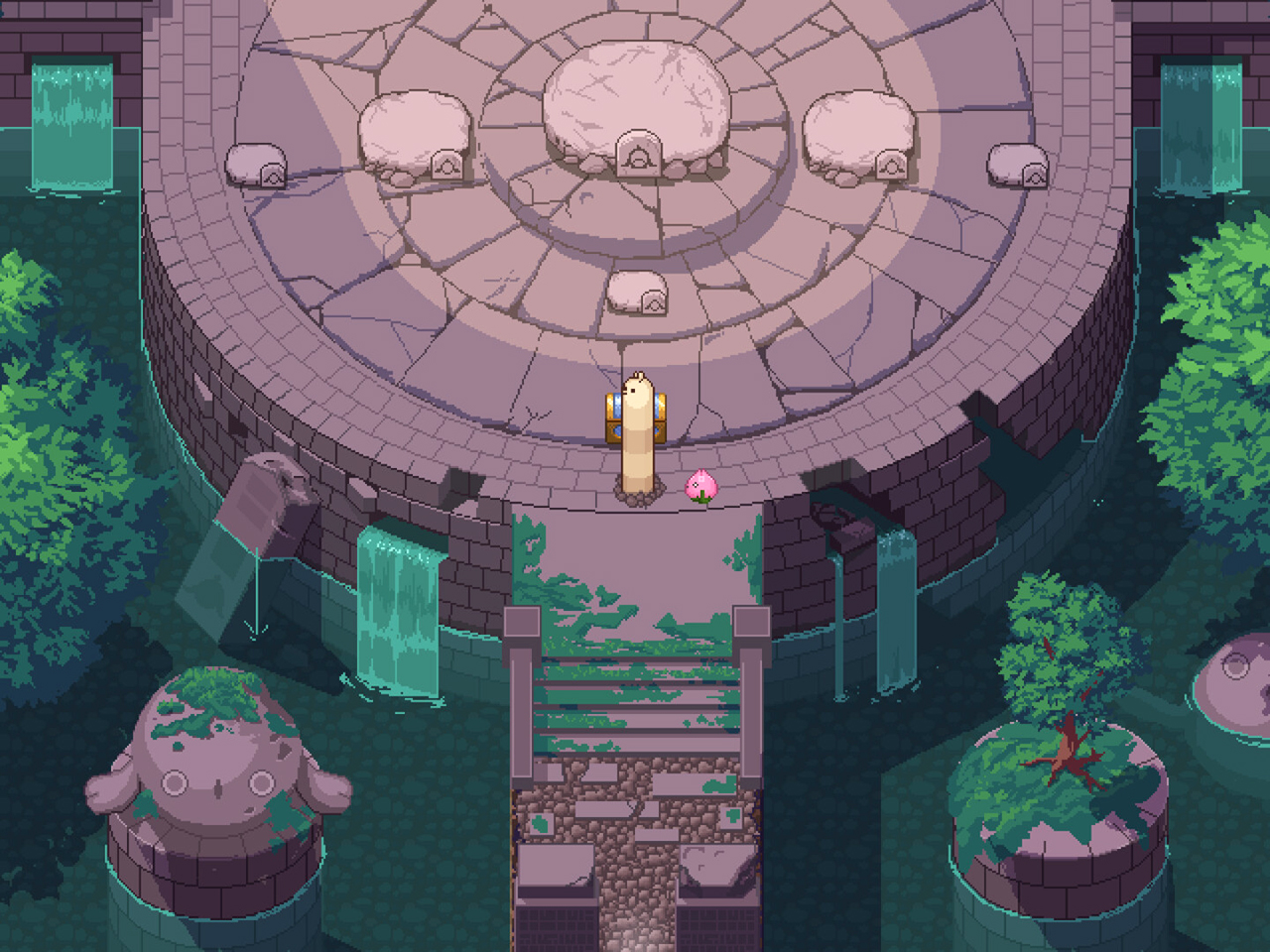

In terms of its playspace, Beacon Pines is relatively small. Not counting a few plot-specific locations that you only visit once, there are about fifteen outdoor screens in the game, along with perhaps half as many indoor screens. Each of these screens is beautifully painted, with each point of interaction clearly indicated.

What gives Beacon Pines a sense of scale is its structure. The game envisions its story as a tree and gives the player the option to make a key choice at each divided branch. While progressing through the separate branches of the story, the player will naturally pick up “charms,” or words that can be used to slightly adjust the narrative at critical points.

You can always return to an earlier choice with zero backtracking when you get a new charm, and the story’s pacing is excellent. The time spent on each branch is relatively short, which makes it easy to remember what’s going on when you switch to another branch. The way everything fits together as you progress is a masterpiece of narrative craftsmanship.

The tone and level of the writing is consistent with Luka’s age, and the first three Harry Potter novels are the easiest analogy. Each character in the expansive cast has a limited yet well-defined personality, and the story scenarios are improbable yet intriguing. There’s not much psychological depth, and the plot is pure fantasy, but I still had a great time with Beacon Pines. It was a pleasant shock the first time I saw the first dead-end branch of the story, which was delightfully morbid.

There’s one true ending of Beacon Pines, but players should expect to see about a dozen premature endings before they get there. In other words, it’s a linear story, but it’s told in a creatively nonlinear manner that takes every “what if” scenario into account. Again, the narrative craftsmanship is superb.

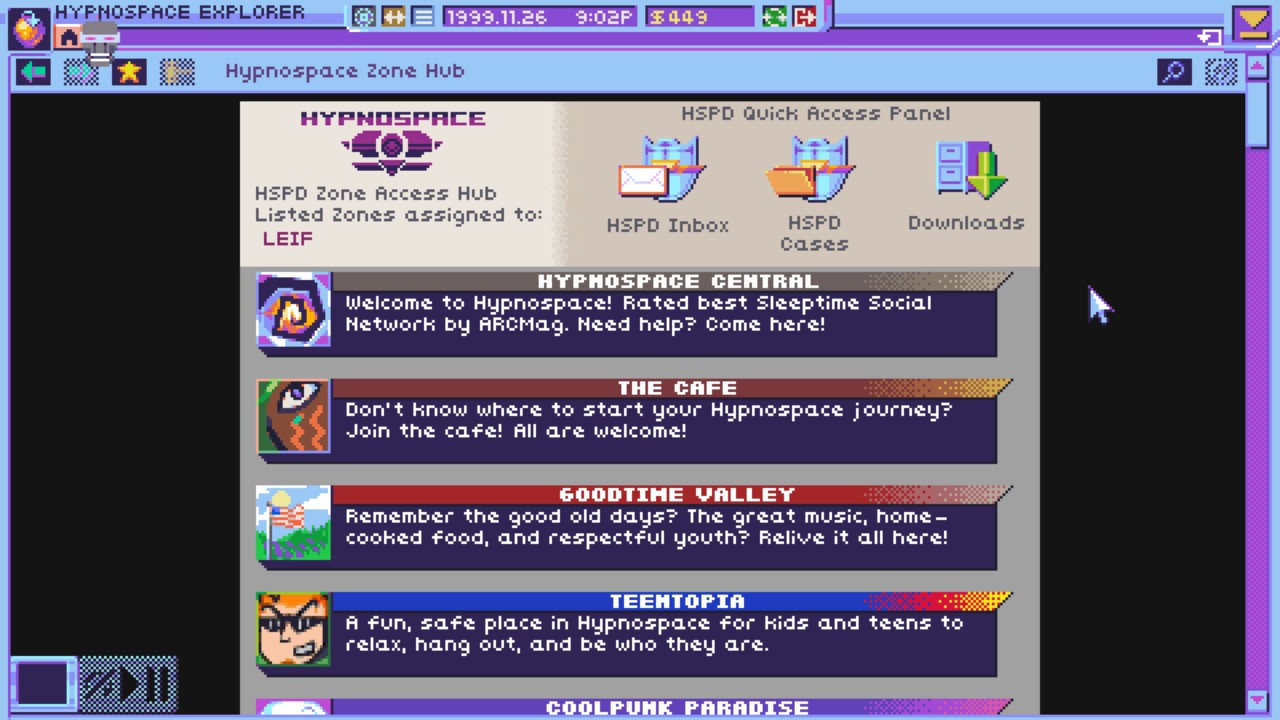

It’s easy to make a comparison with Night in the Woods, as you directly control a character who makes progress by walking around a beautiful small town and talking to every NPC. The themes of the story are similar as well, as the town of Beacon Pines suffers from corporate ownership of its fertilizer factory in the same way that Possum Springs suffers from corporate ownership of its mines. As in Night in the Woods, there are supernatural elements at play, although Beacon Pines is more concerned with mad science than cosmic horror. The major difference is that I wouldn’t give Night in the Woods to a child, while Beacon Pines is suitable for middlegrade (10-14yo) players.

I am not the target audience for “all-ages” fiction, but I enjoyed Beacon Pines regardless. Most of the adult characters in the game are problematic and relatable, and the story’s environmental themes are worth considering beyond a superficial level. The villains are a lot of fun, as are the more horror-themed elements of the plot.

It’s also important to note that the character art is gorgeous. The animal characters were clearly drawn by a furry artist in a way that the characters in Night in the Woods were not, but I have nothing but love for this art style. Despite the relatively large cast of characters, the character designs are all unique and visually interesting. I’m not a furry myself, but I was still able to appreciate the high polish of the art. There is no cringe here, just beauty and creativity.

The environmental art is gorgeous as well. The pleasant façade of Beacon Pines is indeed pleasant, with lovely trees and handsome buildings adorning each screen. Although we don’t see much of the town’s dark secret, the visual design of the spaces it affects fit the theme perfectly.

In terms of gameplay, I always felt directly engaged with the story. There’s nothing missable or collectable, and the game doesn’t get cute with achievements. There are two optional minigames, and they’re both unobtrusive and enjoyable.

Beacon Pines is short, inexpensive, and accessible. If you’re a fan of Night in the Woods, or if you’d like to play a visual novel with more interactivity, I’d definitely recommend giving Beacon Pines a shot. Since it comes off a bit like a generic cozy game on its Steam page, I had no idea Beacon Pines would be as interesting as it is, but it’s an amazing treasure of a game.