Animal Well is a no-combat puzzle platformer with an open-world Metroidvania structure. You play as a small seed navigating a mossy system of underground tunnels. The game has no dialogue or diegetic text, nor does it need any. Your job is simply to explore.

Because this is a video game, however, the player needs objectives. Early on in the game, the little seed arrives in what appears to be a central hub with statues of four animals. Each animal’s flame is sealed in a themed quadrant of the map. Although your map is mostly blank at the beginning, the location of each flame is marked, giving you four goals to work toward. Navigation is anything but simple, however, and figuring out where you’re supposed to go is just as much of a puzzle as any of the one-room set pieces.

Since Animal Well gives you so many paths to choose from, the beginning can be confusing. In many ways, this game reminds me of Hollow Knight and Hyper Light Drifter, which are similarly cagey about where the critical path might lie. Thankfully, there’s no wrong way to play Animal Well, so you’ll be fine if you simply choose a direction and start walking. Once you make your way into a level proper, the path forward becomes much easier to follow.

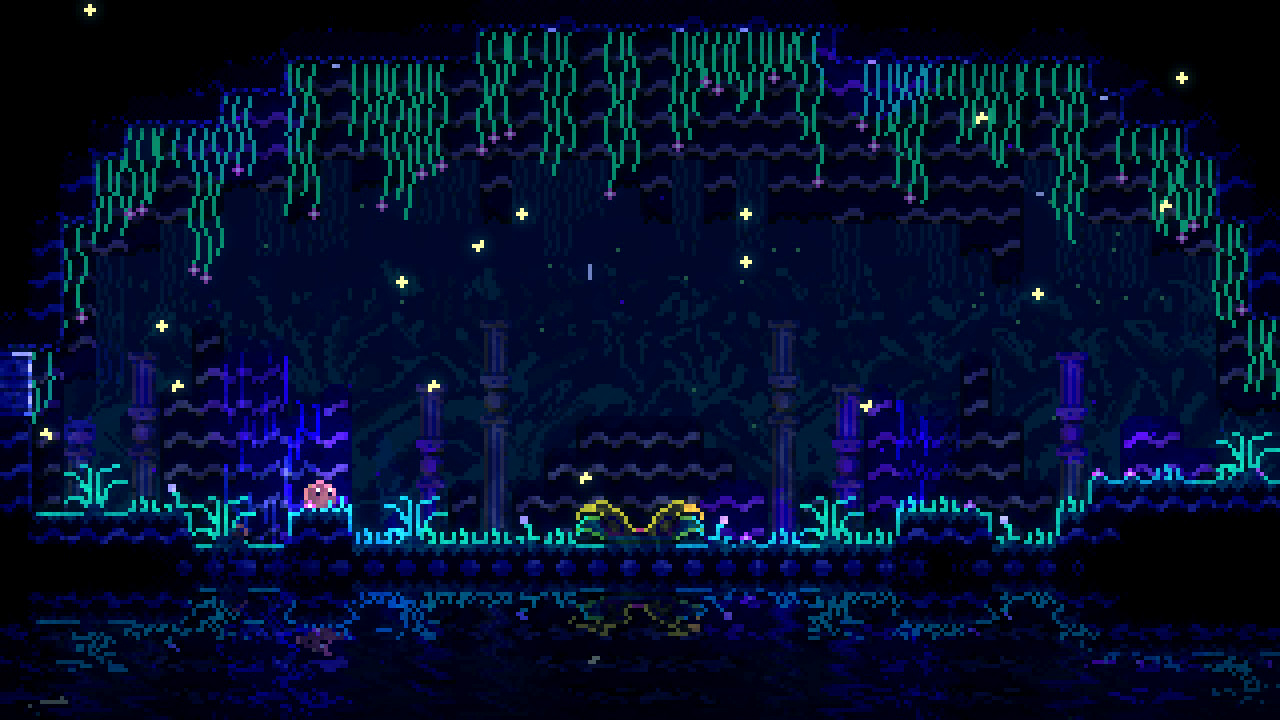

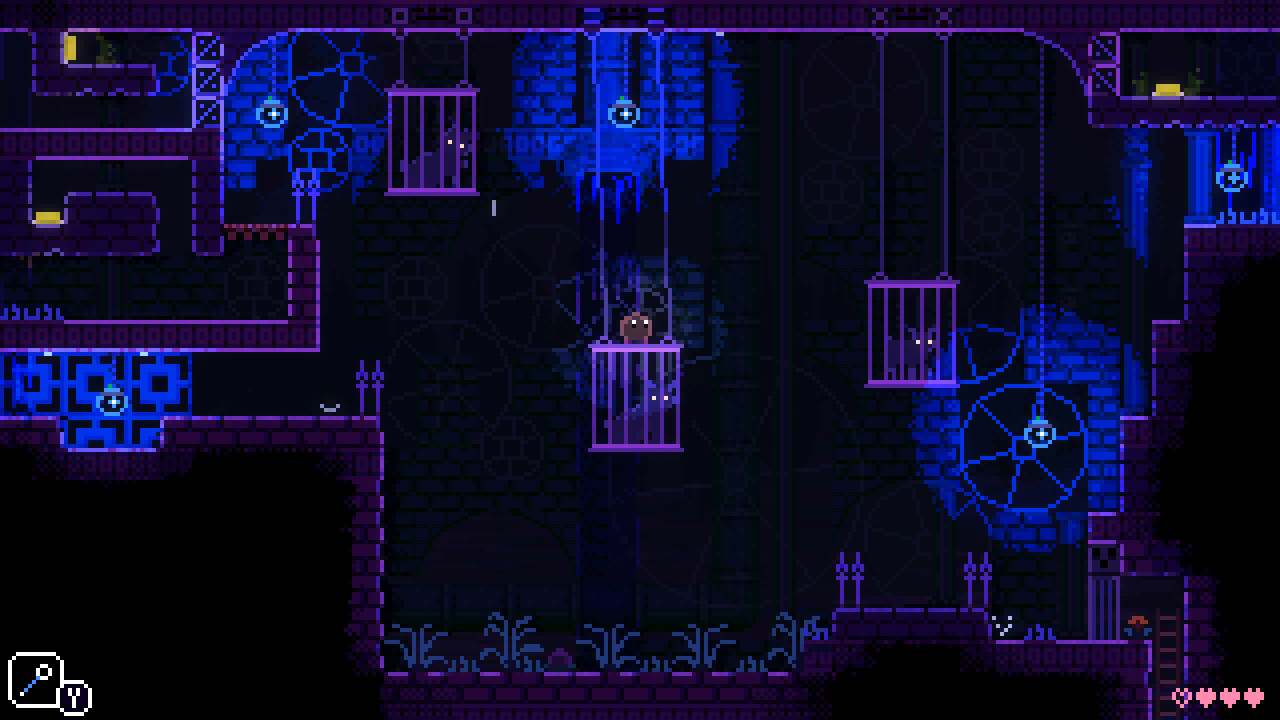

As you might guess from the title, the vast underground well that serves as the setting of the game is filled with animals that theme the puzzles. In the dog level, for example, you’ll need to find a frisbee that you can throw to distract the dogs that chase after you. In the seahorse level, fish blow bubbles into the air that you can use to reach higher platforms. In the chameleon level, you’ll need to adjust the path of wall-climbing hedgehogs so that they hit otherwise inaccessible switches.

Animal Well offers the player a beautiful and evocative environment to get lost in, and it’s nice to see such a well-designed game that focuses on exploration instead of combat. Most of the platforming puzzles are relatively easy but still very clever, which I appreciate. The pixel art is gorgeous and atmospheric, and each area manages to express its theme while still maintaining a unified aesthetic that ties the various ecosystems together. There’s not much music, but the sound design is fantastic.

If I have one complaint about Animal Well, it’s that the map is riddled with secret passageways that are completely unmarked. In addition, you can only make it so far into each level without the aid of a tool from another level. In theory, this means that there are eight levels instead of four. In practice, it can be frustrating not to know whether you can’t proceed because you need a tool from a different level or whether you simply missed a hidden path. Unless you happen to be either very good (or very patient) with this sort of thing, I’d strongly recommend playing Animal Well with a walkthrough.

It’s impossible to say how long Animal Well takes to play. According to reviews, it has the potential to be a five-hour game, but I get the feeling that the majority of players aren’t going to have such a smooth experience. If I had to guess, I’d say that most first-time players should expect to spend at least six or seven hours getting to the end. After that, there’s potentially another ten hours of exploration enabled by the tools you find at the end of the final area.

Is the cleverness and charm of Animal Well worth the aggravation of getting lost and not knowing what you’re supposed to do? That depends on the player, of course, and it’s worth saying that this isn’t a casual game. Still, although I wish Animal Well were less opaque, I appreciate that it’s not actually difficult. Exploration is always rewarded, and I never stopped being surprised and amazed by each new bit of the game I managed to find. Every single screen in Animal Well is a work of art.

After finishing Animal Well, I read the TV Tropes page to see if there’s an actual story to the game. Perhaps you can unlock a different ending if you can manage to find all the collectables? From what I can tell, there’s no real story no matter what you do, but there are collectables underneath collectables underneath collectables. There’s also an ARG. None of that is any of my business, but it’s cool I guess. I always appreciate when the people who created a game were living their best lives, and I’m happy to have an excuse to spend more time poking around the beautiful mossy tunnels of Animal Well.