Whispering Willows (on Steam here) is a 2D adventure game set in a haunted mansion. There’s no combat, and the game takes about three hours to finish. It’s a small indie game made in 2014, and it’s not perfect. Still, I enjoyed the time I spent in Willows Mansion, and I’d recommend giving this game a shot if you’re into spooky gothic stories.

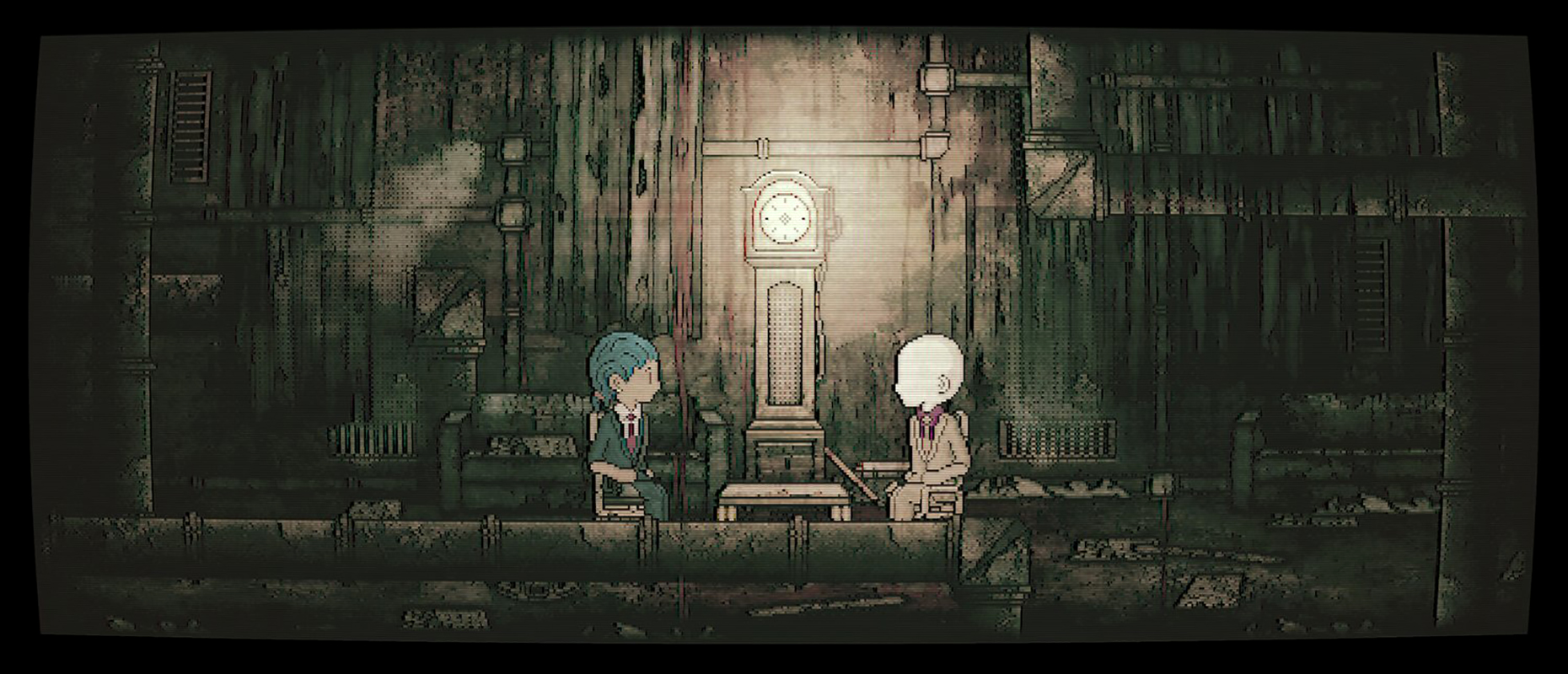

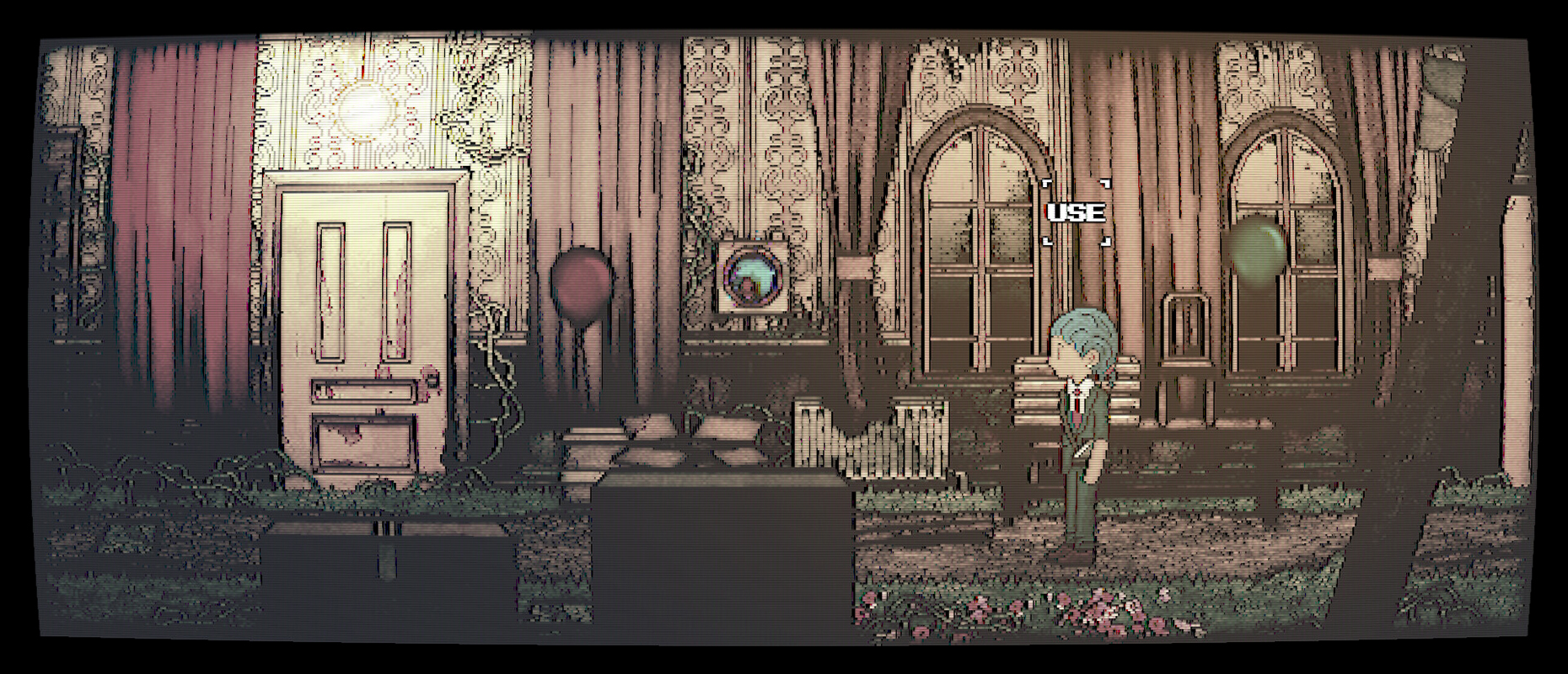

You play as Elena Elkhorn, a teenage girl whose father works as the groundskeeper at the derelict and abandoned Willows Mansion. Elena’s father doesn’t return one night, and she has a bad feeling about the mansion. Hoping to bring her father home, Elena sneaks onto the property and immediately falls headlong into an underground crypt. There she meets the ghost of her ancestor, who teaches her how to use the power of her magical pendant to leave her body to go spiritwalking. In a cursed mansion filled with phantoms, this is an extremely useful ability to have.

Before I jump into the many things I love about this game, let me be upfront about its flaws:

– There’s not much actual gameplay.

– The hand-drawn cutscene art is unpolished.

– The writing is good but a bit uneven.

– The background music is limited.

– Your character walks very slowly.

– There’s no map to help you navigate.

Essentially, this is a small indie game that indeed looks and feels like a small indie game. I’m not complaining about the rough edges of Whispering Willows; I just want to make it clear that it’s a game made ten years ago on a tiny budget earned from a Kickstarter campaign. Still, I found its simplicity and amateurish aspects charming, and it has many strong points.

To begin with, the map is surprisingly large, and there’s a lot of space to navigate. You’ll explore the mansion’s crypt, its garden, and various outbuildings; but mainly you’re going to be walking around the house itself. The mansion is impossibly large and includes all the standard gothic flourishes: locked doors, grisly kitchens, moldy bathrooms, crooked paintings, peeling wallpaper, taxidermied hunting trophies, creepy dolls, and all the secret passageways you could ever want.

Of course there are all manner of notes lying around, and these notes collectively tell a suitably gothic story about the very wealthy but very evil man who built the mansion. This story never quite comes together in terms of plot or themes, and the character motivations are ridiculous. Still, all the individual bits and pieces are gothic catnip, from a lover kept in a secret room to a murdered best friend to a servant driven mad by what he’s seen.

This all takes place in California during the Wild West days, meaning that the land occupied by the mansion had to be taken from someone. It turns out that it was forcibly wrested from Elena’s own ancestors. Alongside his more intimate crimes, then, the mansion’s owner became the mayor of a frontier town by means of enacting war and genocide on First Nations people.

We tend to think of gothic mansions as being located in Europe, or perhaps New England. There are definitely nineteenth-century mansions in California, though (like the Carson Mansion), and they’re built on land soaked in blood.

Importantly, the First Nations people in Whispering Willows aren’t all ghosts. Elena and her father are very much alive, and they’re not tempted by the faded pseudo-grandeur of the former colonists. At the end of the game, it’s extremely satisfying to see Elena essentially say “fuck all this” as she walks away from the mansion with her father.

This is an interesting perspective on classic gothic story tropes that I love to see. And honestly, Whispering Willows isn’t such a bad game. The puzzles are easy, but the lack of difficulty is a selling point for me. Also, the gameplay mechanic of Elena spiritwalking to interact with the numinous aspects of the environment is used in clever ways, and it’s a lot of fun.

Aside from Elena’s slow walking speed, my only real complaint is that this game would benefit immensely from a map. Even though navigation isn’t particularly complicated, I got lost a few times and had to resort to a walkthrough (this one here) a few times, which wouldn’t have been necessary if the player could just pull up a subscreen.

Whispering Willows definitely feels like an indie game, but it’s got a delightfully grisly story and an excellent sense of atmosphere, and it’s worth checking out if you’re interested in Wild West Gothic from an indigenous perspective.

As a side note, this was apparently the game that launched Akupara Games, a publisher that specializes in quirky indie games with a strong sense of style and setting. Two of my favorite titles they’ve helped get off the ground are Rain World and Mutazione, and it’s cool to know that this was where they started.