In order for a story to be considered “Gothic,” I think it needs to include…

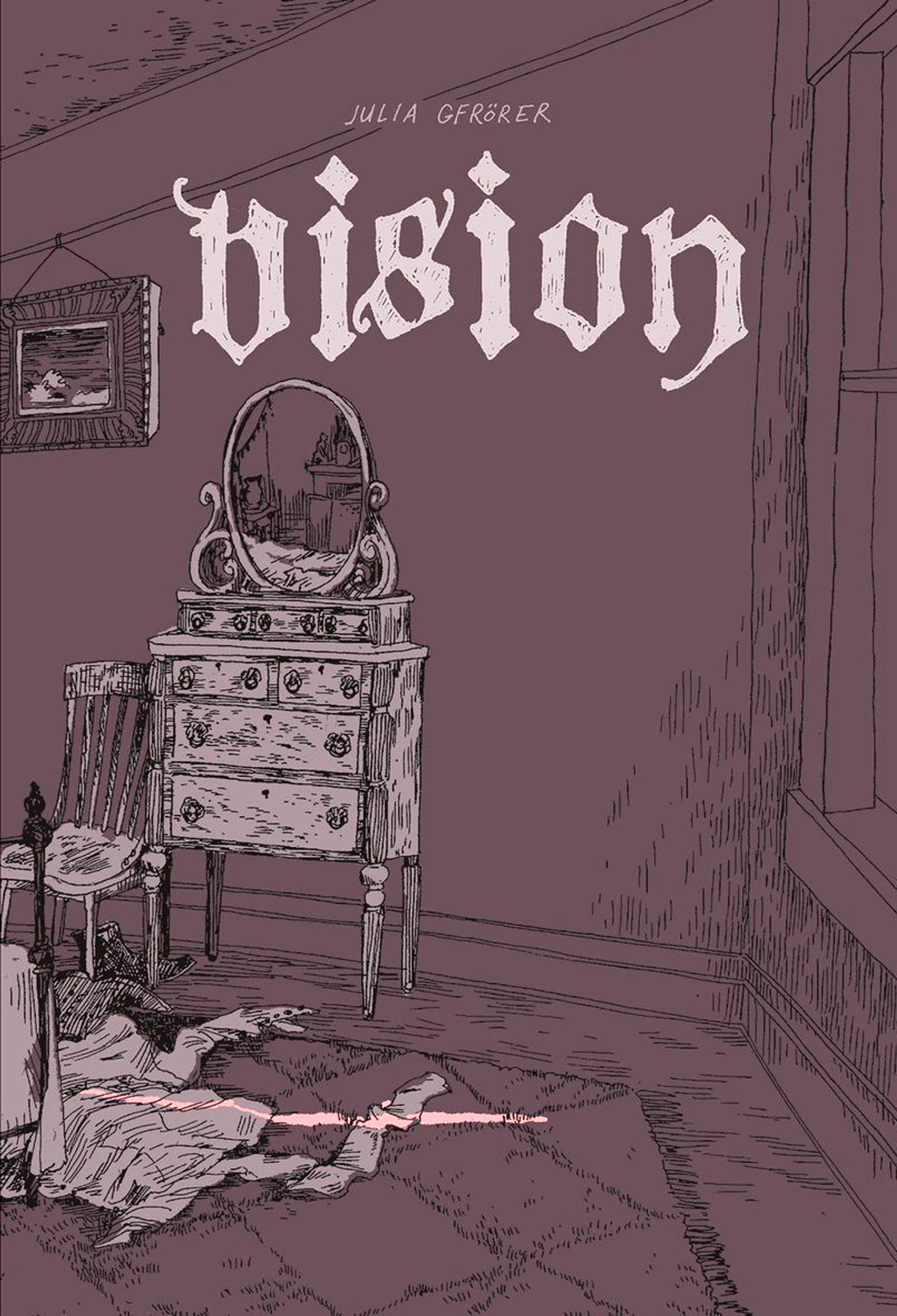

– A house. This “house” can be a castle or a space station or an abandoned medical research facility or what have you, but it needs to be a place where people live and eat and sleep.

– It has to be a big house. In addition to being big on the outside, it should be larger than it appears. The house should have something along the lines of a secret sub-basement, hidden rooms, tunnels in the walls, a House of Leaves style portal to another dimension, or something along those lines. The house needs to be large enough to be considered a labyrinth.

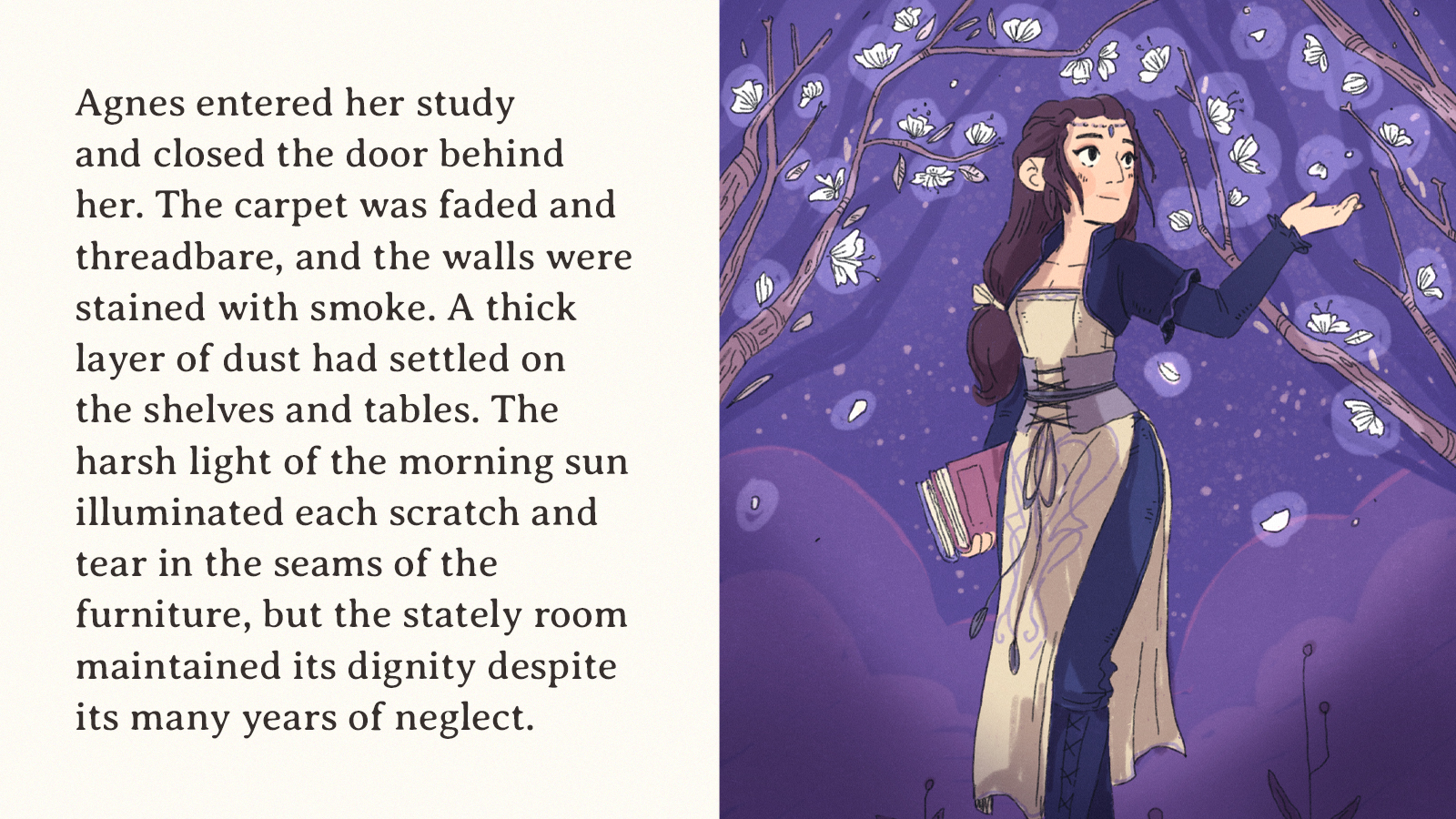

– The house has to be old and in a state of decay or disrepair. In addition, the house needs to be isolated and surrounded by wilderness. Over the course of the story, the natural environment should intrude on the interior of the house. This should still be the case even if the environment is not technically “natural,” as in the case of Suburban Gothic.

– The house needs to be associated with and occupied by a family.

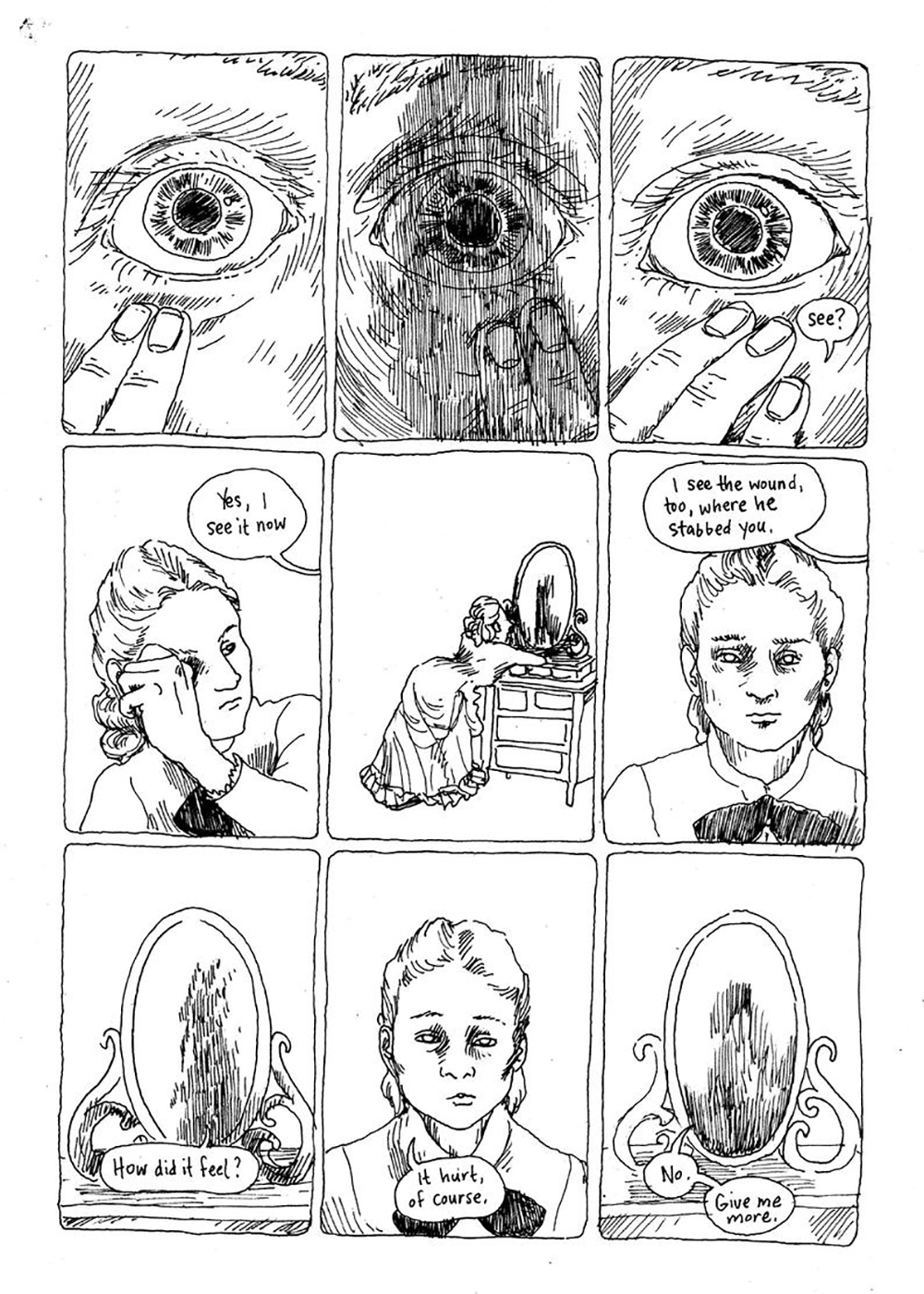

– The family needs to have a dark secret, preferably one hidden within the house.

– At least one member of the family should still live in the house. “Family” can be loosely defined, but the concept of “family” as such is key.

– If there’s no family living in the house, then the story is a “haunted house” story, not a “Gothic” story. This is also the case if the people living in the house aren’t alive or aren’t human (or whatever passes for “a normative person” in the world of the story). This is important, as “Gothic” is just as much of a narrative structure as it is a collection of tropes. For example…

– The point-of-view character should be a member of the family in some way. Often this character will come into the house through marriage or inheritance. Sometimes they won’t initially know they’re related to the family. In the case of servants and governesses and so on, the point-of-view character will either be secretly related to the family, or they’ll be a parent or spouse in all but name. If the point-of-view character isn’t related to the family, they will gradually fall under the delusion that they are.

– The point-of-view character will obviously be privileged, as they live in a large house and are associated with a wealthy family, but they also need to be disadvantaged in some way. The way in which they’re disadvantaged should have some thematic relevance to the dark secret hidden by the house.

– The point-of-view character must be forbidden from certain behavior by an arcane rule or system of rules. The forbidden behavior will generally involve the navigation of space in or around the house: Don’t go into the forest, don’t go into the cellar, don’t leave your room at night, etc.

– The disadvantage of the point-of-view character will compel them to accept the family rules even though they can intuitively feel that something is horribly wrong. This traps them within the house.

– The goal of the point-of-view character is to escape the maze of the house. The only way to navigate this labyrinth is by breaking the rules, engaging in forbidden behavior, and bringing the dark secret to light.

– The primary antagonist should be a living person in the family, related to the family, or emotionally invested in the family in some way. Although supernatural elements are not out of the question, it’s often the case that the phenomena presumed to be supernatural have a rational (albeit psychologically deranged) explanation. That being said, there’s often a Todorovian elision between “natural” and “supernatural,” with the distinction being left to the reader.

– When the point-of-view character reveals the family’s secret, this destroys the house. This destruction is usually literal. The family almost always dies as well. If the point-of-view character is too closely tied to the family, they may die too. Regardless, the reader will understand that the collapse of the house and the demise of the family is a good thing that needed to happen.

– The house and family should represent an older social system responsible for the disadvantage of a group of people represented by the point-of-view character. This system usually concerns oppression on the basis of class or gender, but it can sometimes be about race, nationality, or colonial heritage.

– The Gothic genre is not conservative, because it’s essentially about how outdated systems of privilege that still continue to oppress people are deeply fucked up and unhealthy and need to be destroyed. “Haunted house” stories are often conservative, but I would argue that Gothic stories advocate for radical systemic change and the self-realization of freedom from social expectations.

– At the same time, Gothic stories are not didactic. The lure of the forbidden goes both ways, after all, and the reader should be able to understand why the point-of-view character allows themselves to become trapped in the house. The old castle is majestic. The beast-husband is attractive. The spoils of ill-gotten wealth are luxurious and comfortable. The ruins are delightfully mysterious. The poison apple looks delicious. The story is queer and problematic, and that’s precisely why it’s appealing.

There are numerous cross-genres and sub-genres of Gothic that have their own specific conventions, like Gothic Romance and Boarding School Gothic. I didn’t address the visual language of the Gothic, or how tropes and conventions vary between times and cultures. Still, I think this is the core of the genre.