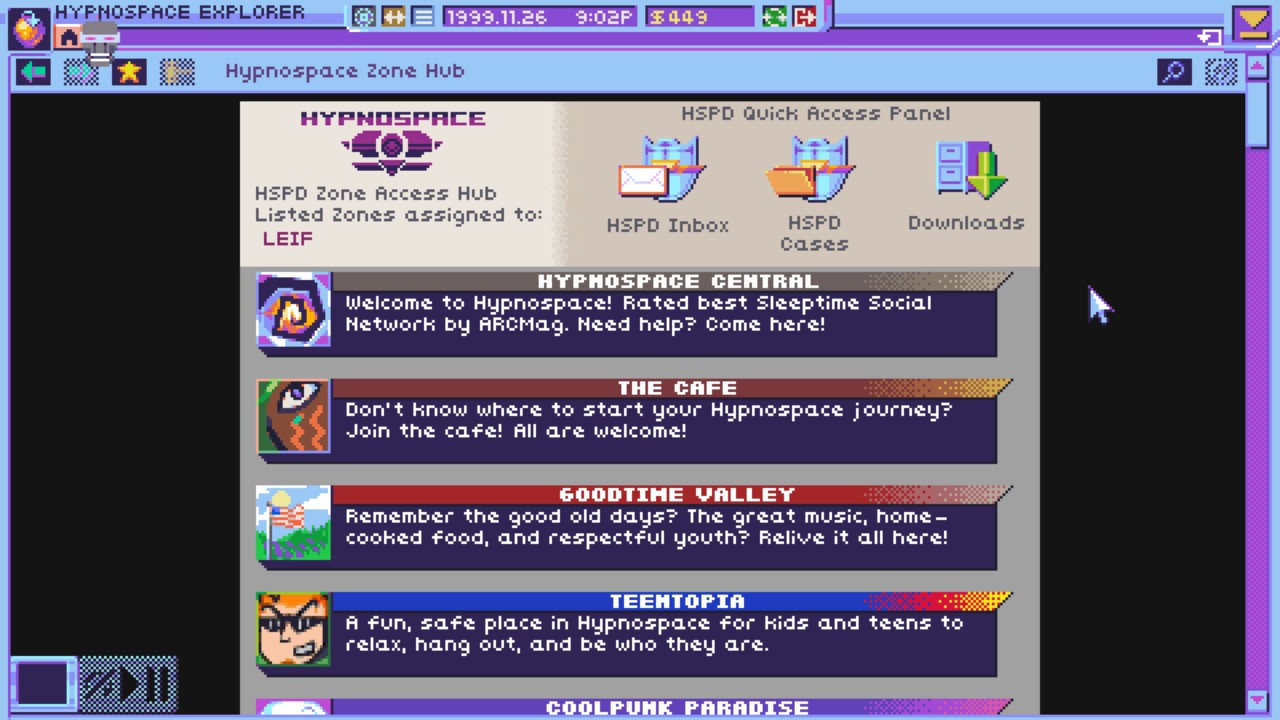

Hypnospace Outlaw is an internet detective game set in a parallel universe in 1999. You play as a volunteer moderator who’s tasked with flagging content violations, and the gamespace consists of your desktop, your email inbox, and a web browser that connects you to Hypnospace, a Geocities-style database of websites.

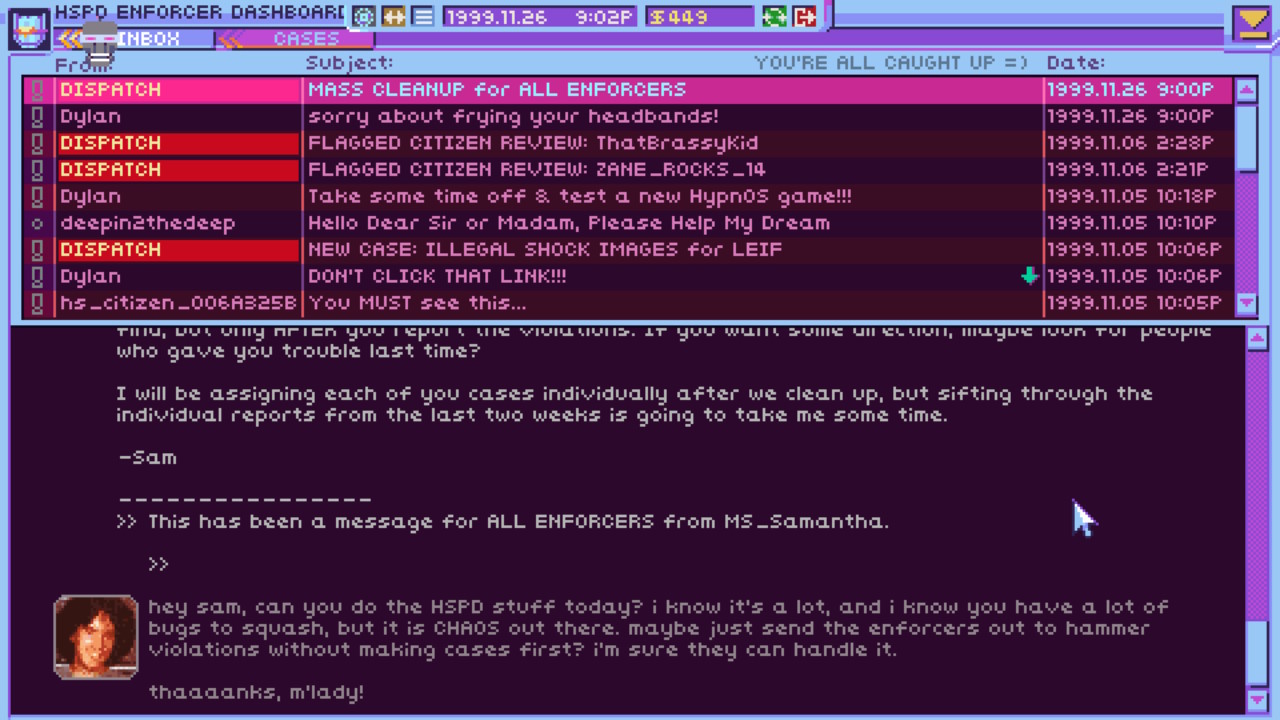

The Hypnospace admins send you a series of cases, and the first one is easy enough to solve. A representative of the estate of an artist who created a popular cartoon character has reported a page displaying unauthorized reproductions. You can find the page easily enough by searching for the character’s name in your web browser, where you see that a first grade teacher has shared scans of her students’ artwork of the character. You can click on each image and use a special tool in your browser to report it, thus removing the artwork from the woman’s page. Once you’ve removed all images recognizable as the character, you’ll get an email telling you that the case is resolved.

Obviously this is a shitty thing to have done, but the game doesn’t give you any ability to do otherwise. If you want to keep playing, you have to “solve” these cases in the only manner provided. Unfortunately, it’s not possible to make choices.

This lack of agency can be upsetting, especially when the game forces you to slap violation penalties on a teenage girl experiencing sexual harassment through DMs. She sent a support request to Hypnospace asking them to address the harassment, and she’s posted screenshots of the chats on her page. When you report these images as harassment, the girl is the one who’s penalized, as the images are hosted on her page.

A female member of the admin staff carbon-copies you on an email that she sends to her boss, asking him if this misattribution can be corrected. Unfortunately, he’s a piece of shit and brushes her off, saying that it’s not his problem. M’lady.

The point of being able to see the internal workings of content moderation is to give the player a sense of how wild and woolly the early public internet used to be. The administrators and moderators managing online communities were young and didn’t really know what they were doing, and there was a complete disconnect between corporate software developers and the end users, many of whom were just kids. In addition to teen drama, Hypnospace also hosts retirees with time on their hands, people who are deeply emotionally invested in the music they enjoy, small businesses doing their best, and a healthy cohort of amateur artists and poets.

Hypnospace Outlaw has a strong Windows 95/98 aesthetic, and the Geocities/Angelfire style of page design is well-observed, with ample crunchy backgrounds and neon colors and spinning GIFs. What’s less well-observed is the quality of the writing people put on their pages. Even in college in the mid-2000s, I remember finding this exact style of personal webpage and being impressed by how knowledgeable and competently written they were. In Hypnospace Outlaw, however, the writing is uniformly bad. It’s bad on purpose, which has its charm, but I still got the feeling that the in-game webpages are more to look at than to read.

If you can tolerate the bad-on-purpose writing, however, all sorts of intriguing worldbuilding details begin to emerge. You never learn much, however, only bits and pieces of trivia that are incorporated into people’s discussions of their special interests. The main “alternate” aspect of this universe, which is that people access the internet by wearing a headband while they sleep, is never explained. It’s also not particularly important… until it is. Still, I wouldn’t say that Hypnospace Outlaw has anything as structured as a plot. You’re mainly just here for the vibes.

After the first case, the game becomes infinitely more difficult and complicated, and I had to make constant use of a walkthrough (this one here). I have no idea how I would have figured out many of the cases otherwise. The problem is that there are dozens of public pages, not to mention hidden pages and directories and search terms and tagging systems, and the “clues” you receive are all extremely cryptic. There’s a lot of noise and not much clarity.

In the end, I’d estimate that it’s completely unnecessary to engage with about 70% of the game. There’s no real incentive to sort through the chaff unless you’re simply curious and don’t mind spending time clicking on links and reading through the webpages collected in the various themed directories. I ended up ignoring a lot of the game’s content, but I really enjoyed the pages that focus on urban legends and conspiracy theories. There’s also a page devoted to a kind of lo-fi, found-noise techno called Fungus Scene that I would very much like to exist in our own universe. Personally speaking, I would have preferred more of this sort of “weird but brilliant” creativity and less “kids being immature” cringe humor.

If you beeline through the cases with a walkthrough, Hypnospace Outlaw takes about three to four hours to finish, and how much time you’re willing to spend exploring outside the main objectives will depend on your tolerance for this subjective version of what the internet looked like in the late 1990s. For me, Hypnospace Outlaw is interesting in theory but somewhat frustrating to engage with, and the ultimate message that incompetent techbros can get away with everything from harassment to manslaughter didn’t really resonate as a meaningful story.

Still, despite routinely subjecting myself to some of the strangest titles Itch.io has to offer, I’ve never seen anything like Hypnospace Outlaw, and I’m happy it exists. If you’re at all curious, I’d recommend checking out the free demo. It’s available for the Nintendo Switch, so you can play the game while smoking weed in the bath, which is probably the best way to experience it to be honest.