Usurper Ghoul

https://evandahm.itch.io/usurper-ghoul

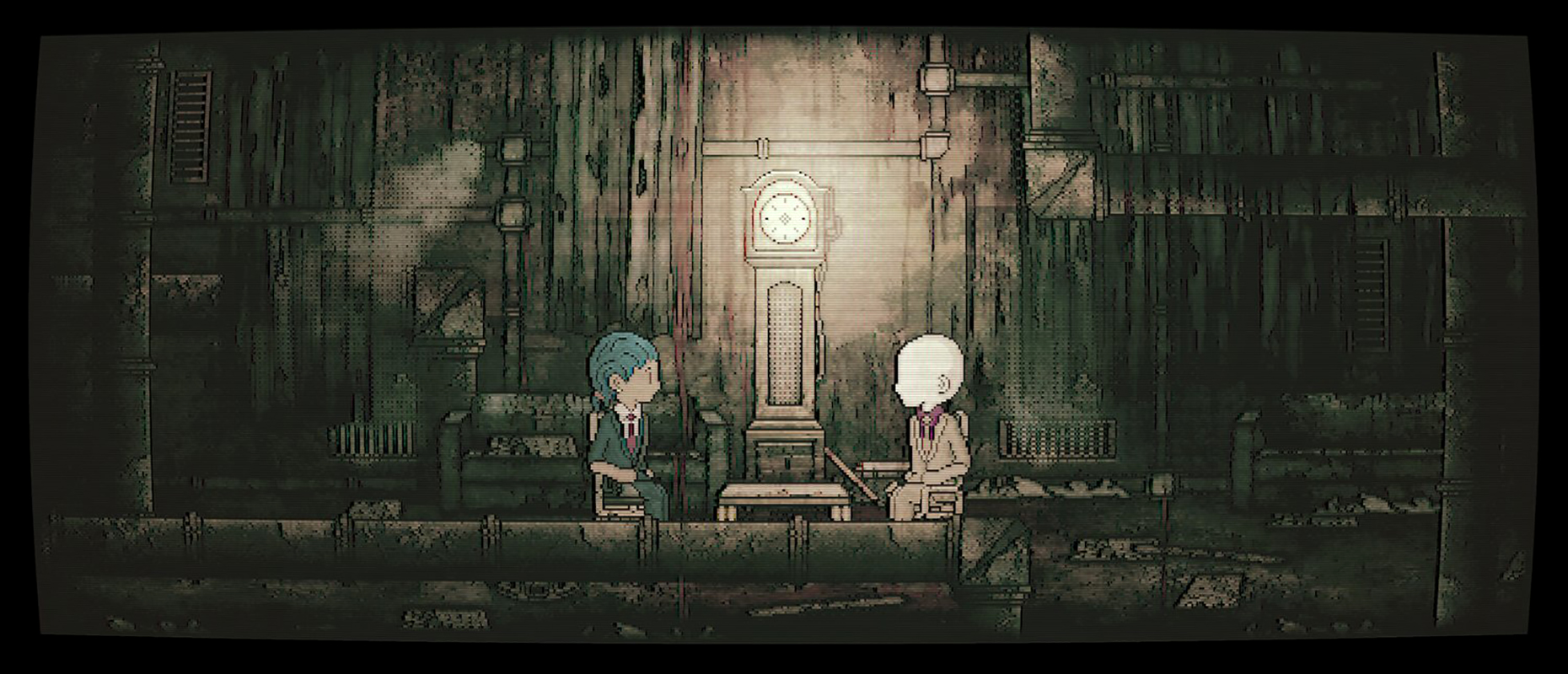

Usurper Ghoul is a nonviolent Game Boy adventure game that channels the “ruined kingdom” vibe of Dark Souls. I tend to think that Dark Souls is marred by needless difficulty; and, in the same way, the gameplay elements of Usurper Ghoul are needlessly frustrating. The nonlinear exploration-based gameplay of Usurper Ghoul is on brand for a Soulslike Game Boy game, but it’s not for everyone. Like Dark Souls, Usurper Ghoul becomes more interesting the more you engage with it, but the beginning is rough.

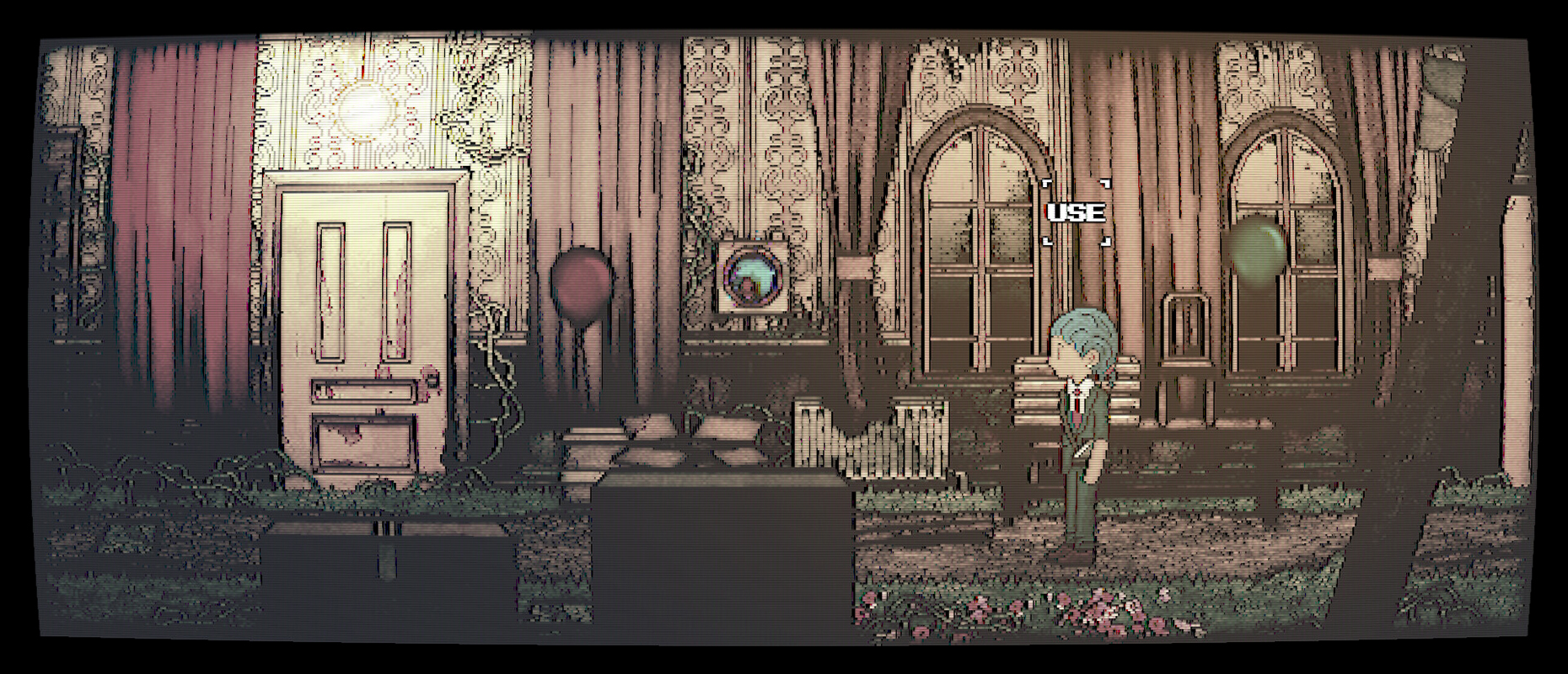

You play as a horned, skull-headed demon who wakes in a garden in the hills overlooking a small village, which in turn overlooks a valley of tombs. In true Dark Souls fashion, no one tells you where to go or what you need to do, and it’s possible to spend a lot of time walking around without getting anywhere. There are a few people scattered across the wilderness, but they’re not particularly helpful.

With no particular goal other than to explore the world, your job is to collect three items from three categories. Flowers allow you to interact with people, sticks allow you to interact with the environment, and rocks allow you to access more knowledge about the world. One stick allows you to unlock doors, for example, while another stick allows you to read written text. The catch is that you can only hold one of each type of item at a time.

The necessity of discarding one item in order to use another fits the broader theme of the game, which is that something must be sacrificed in order for something else to be gained. Unfortunately, switching between items involves a great deal of needless backtracking. The world of Usurper Ghoul isn’t that big, and the game isn’t overly complicated, but it’s big and complicated enough for the backtracking to be annoying. There are no puzzles involved; it’s just donkey work.

One might say that Dark Souls involves needless complications and barriers to progress, but one of the primary attractions of Dark Souls is that it’s gorgeous to look at. You might be continually frustrated over the course of your journey through Lordran, but you tolerate the setbacks because the environment is so beautiful and atmospheric. The world design of Usurper Ghoul is unique and interesting, to be sure, but it’s still rendered with primitive Game Boy graphics. There’s no background music, and the sound design is limited to jarring beeps at odd moments. In other words, it’s not necessarily a pleasure to trek back and forth across the map to switch out one tool for another.

The overall story of Usurper Ghoul is intriguing, but the writing is hit or miss. Most NPCs say decontextualized NPC banalities, and the lore encountered in books and on monuments often feels like a parody of Dark Souls. Although this is never explained, your goal is to enter a tower; and, to do so, you have to collect enough lore to figure out the right order to light torches in front of the tombs in the valley. You need different sticks to unlock gates, to read the writing on the tombs, and to light their torches, so this is a tedious process even if you (like me) lose patience with the game’s obtuse writing and resort to a walkthrough to figure out the order.

Having discussed what’s frustrating about Usurper Ghoul, I now want to explain why I enjoyed it anyway. The next paragraph contains mild gameplay spoilers, but it’s also the coolest part of the game.

For your own nefarious purposes, you can offer three varieties of flowers to NPCs. Comely flowers make people like you, malodorous flowers make people dislike you, and horrid flowers will kill anyone who touches them (except you). In one of the game’s endings, you can climb the tower in the valley and simply leave the kingdom behind without hurting anyone. If you want to experience everything Usurper King has to offer, however, your goal becomes to kill as many NPCs as possible while managing the limitations imposed by each death. Each NPC you kill with a horrid flower leaves a book in the tower whose text emphasizes the theme of sacrifice. For me, this was when the story became worth the trouble of navigating the world.

I found the endgame of Usurper Ghoul to be extremely compelling. And really, despite the initial annoyances, the ideas informing Usurper Ghoul are brilliant. I feel that the success of the execution is limited by the Game Boy technology, and I’d like to give the developer a nice chunk of cash to hire collaborators and develop these ideas into a less bare-bones format, perhaps along the lines of Tunic. Usurper Ghoul is a fascinating proof of concept; and, with a bit of polish, I could easily imagine it becoming a cult classic.

For me, the payoff of Usurper Ghoul was worth the frustration of the gameplay and the occasional Dark Fantasy Generator™ writing, but your mileage may vary. There’s a lot to explore and experiment with in the world of the game, and it’s definitely possible to spend several hours there. I lost patience toward the middle and used (this walkthrough on Reddit) to smooth over some of the rougher bits, and I ended up spending a bit more than two hours with the game. If nothing else, I’m really looking forward to checking out the developer’s comic projects in the near future.