Misao is a short 16-bit indie survival horror game originally released in 2011 and then published on Steam (here) as a remastered edition in 2024. The game is set in a high school that’s been transported to a demonic realm by the vengeful spirit of the eponymous Misao, a beautiful but quiet girl who mysteriously disappeared three months prior to the opening of the story.

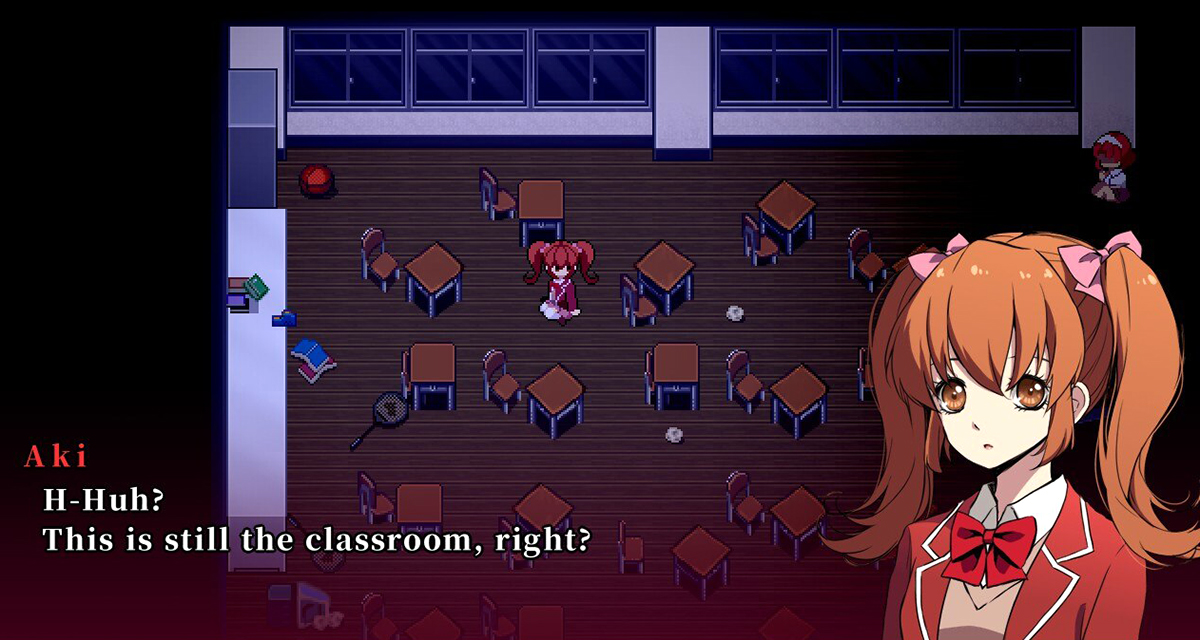

You play as a girl (or optionally as a boy, in the HD version) named Aki who suddenly hears Misao’s voice in the middle of class, asking someone to “find me.” The classroom is cloaked in darkness, an earthquake hits, and the school begins to fall apart in the aftershocks. As Aki explores the mostly abandoned building, she learns that four of her classmates were bullying Misao with the compliance of their homeroom teacher. Despite the intensity of the bullying, Misao didn’t kill herself – but someone else did.

The gameplay consists of navigating the school while collecting six objects necessary to piece together Misao’s story. There’s no set order to acquiring these items, meaning that the game starts off as somewhat confounding but gradually comes to make more sense. Once you get your bearings, what you need to do becomes fairly self-evident, but a walkthrough is recommended for players (such as myself) who might find themselves overwhelmed at first. There are several excellent guides posted to Steam, but I recommend (this one) on account of its helpful division into sections.

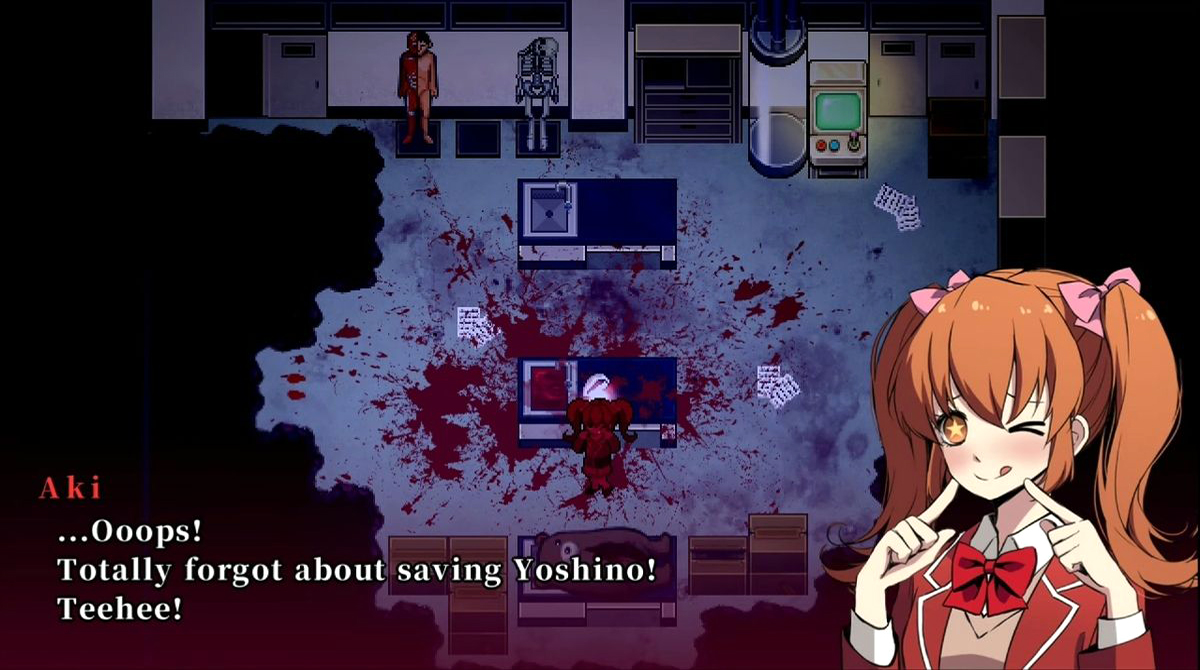

Like Mad Father (reviewed here), which was also published by Miscreant’s Room, Misao is essentially a haunted house simulator in which your player-character can die in dozens of delightfully gruesome ways. Thanks to a handy quicksave function, there’s no penalty for dying, and the player is encouraged to get into all sorts of trouble for the sole purpose of seeing what will happen. Aside from two short chase sequences, very little skill is needed to survive, just a bit of trial and error.

What I love about Misao is how much fun this game has with the tropes and imagery of a haunted high school. The laboratory is staffed by a mad scientist who has a chainsaw and will take advantage of any excuse to use it. The hamburgers in the cafeteria are made of unspeakable meat, and the seating area in front of the open kitchen is filthy with blood and entrails. The toilets haven’t been cleaned for a very long time, nor has the secret zombie cave under the school. The Shinto shrine in the courtyard is beautiful, but the rituals performed there are anything but.

Misao’s story mixes high school bullying and friendship drama with a mystery surrounding a twisted serial killer, and everyone gets exactly what they deserve. Still, for players who think high school kids shouldn’t be condemned to eternal damnation, Aki can rescue her classmates from their personal hells in a short epilogue. A few of the characters Aki encounters are native to the demon realm, and they’re all having the time of their lives. My favorite is the student librarian, who’s fully aware of the bloodshed surrounding her but just wants to make friends. She is a treasure.

If you’re not a completionist, Misao takes about two hours to finish, allowing the story to make an impact without testing the player’s patience through needless puzzles or gameplay challenges. The haunted high school setting is creatively rendered and a lot of fun to explore, even if the open-world structure is a bit overwhelming at the beginning.

The deaths are all creative and disturbing, but the retro graphics allow the game to feel campy instead of creepy, so much so that Misao sometimes feels more like a comedy than a horror story. I grew to feel a begrudging sort of affection for the characters, but I can’t deny that I had a huge smile on my face as I watched them get picked off – and really, good for Misao. I support her.