Bloodbark

https://sirtartarus.itch.io/bloodbark

Bloodbark is a forest horror game based on the art of Eduardo Valdés-Hevia that’s free to download and takes about half an hour to play. You play as a lumberjack camping out in a small cabin next to a state park where a new type of tree has been discovered. Although these trees look like normal birches on the outside, their wood is bright red and fetches a high price. The lumberjack’s job is simple – he needs to find the special trees on his employer’s fenced-in property, cut them down, and return the timber to his cabin.

Still, given how much blood is involved… Are you really sure that it’s trees you’re chopping?

The gameplay of Bloodbark is limited to wandering around (with tank controls) and striking various objects with your axe. As you walk, your character’s thoughts automatically appear on the screen as text overlay. The lumberjack is somewhat unwell at the beginning of the game, and he becomes progressively more unhinged as the days pass. Fun times!

The standard route of progression through Bloodbark is fairly well signposted and easy to follow. If you like, however, you can wander to your heart’s content, and the game features a number of achievements and collectibles. Though it won’t have any effect in most circumstances, you can also hack at anything you like. My favorite surprise in the game is a large cocoon suspended from a pole on a dock at the lake. If you manage to find it and get it open, you’re in for an odd little treat.

Although the twist to the story is nothing you wouldn’t expect, the writing leaves a number of interesting questions open to the player’s interpretation. I am not unsympathetic to the lumberjack, who has reasonable doubts about the job he’s been paid to do, and I’m just as annoyed as he is by the car alarms and other annoyances from the neighboring state park. I also think it’s telling that the lumberjack won’t cut down any tree he’s not paid for, no matter how hard the player tries.

My only issue with Bloodbark is that it conveys “darkness” by turning the visual contrast down to zero. Unless you play the game in a sealed room with no external light, the screen appears to be almost solid black. Depending on the quality of your monitor, the parts of the game that take place at night can range from needlessly annoying to impossible to see. It’s a shame, but I’m afraid that this flaw in the game’s visual design may make it inaccessible to many players.

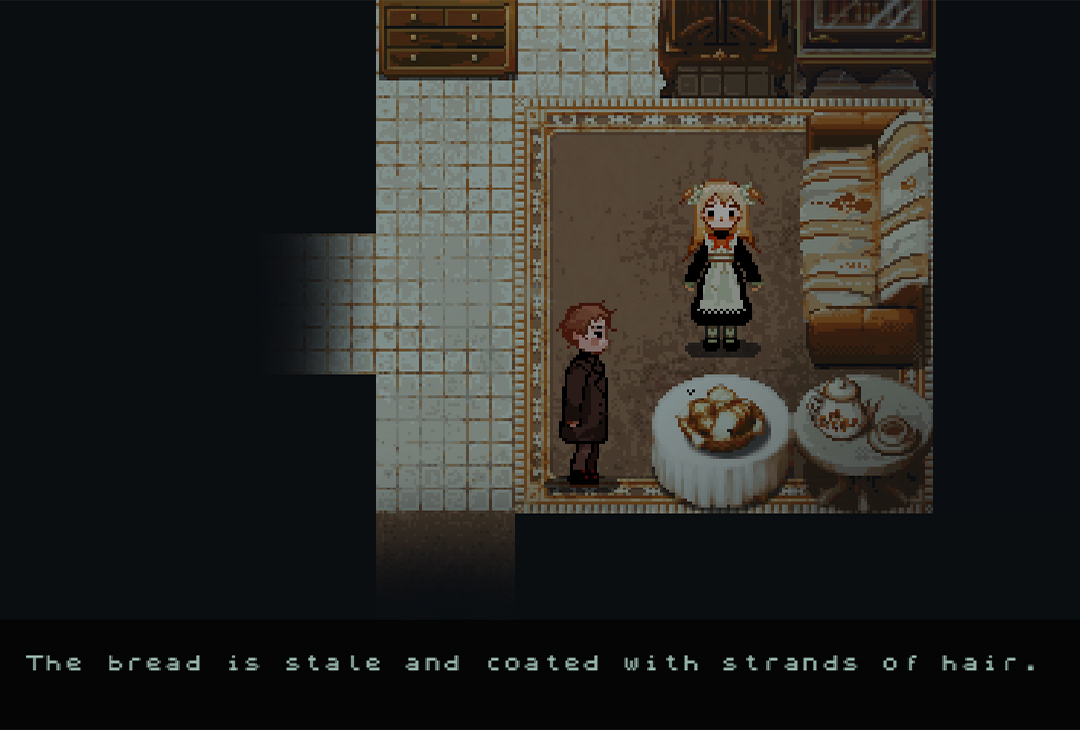

Thankfully, when you can see the game’s graphics, they’re quite lovely. I’m a fan of this sort of lo-fi crispiness to begin with, and I think it creates an interesting contrast with the visual style of many of the secrets you can encounter. To give an example, interacting with three roadside crosses will trigger the brief appearance of a Biblically accurate angel, and the fluidity of this manifestation is a sight to behold against the pixelated mountains and treetops.

If you’re unable to play Bloodbark yourself due to accessibility issues, I’d recommend (this video), which has no voiceover and allows you to watch a streamlined yet still thorough run of the game. Whether you’re watching the game or playing it yourself, Bloodbark is an oddly relaxing game about losing your sanity in the woods, and I’d recommend it to anyone who enjoys the themes and imagery of horror but is happy to dispense with the tension and jumpscares.