Castaway is a tribute to Link’s Awakening whose story campaign takes about 35 minutes to play. This campaign functions as a tutorial to the game’s Death Tower, in which you have one life to climb fifty simple and static floors with very few health drops and no permanent upgrades. The Death Tower is not for me, but the story campaign was a pocket of pure and unadulterated joy.

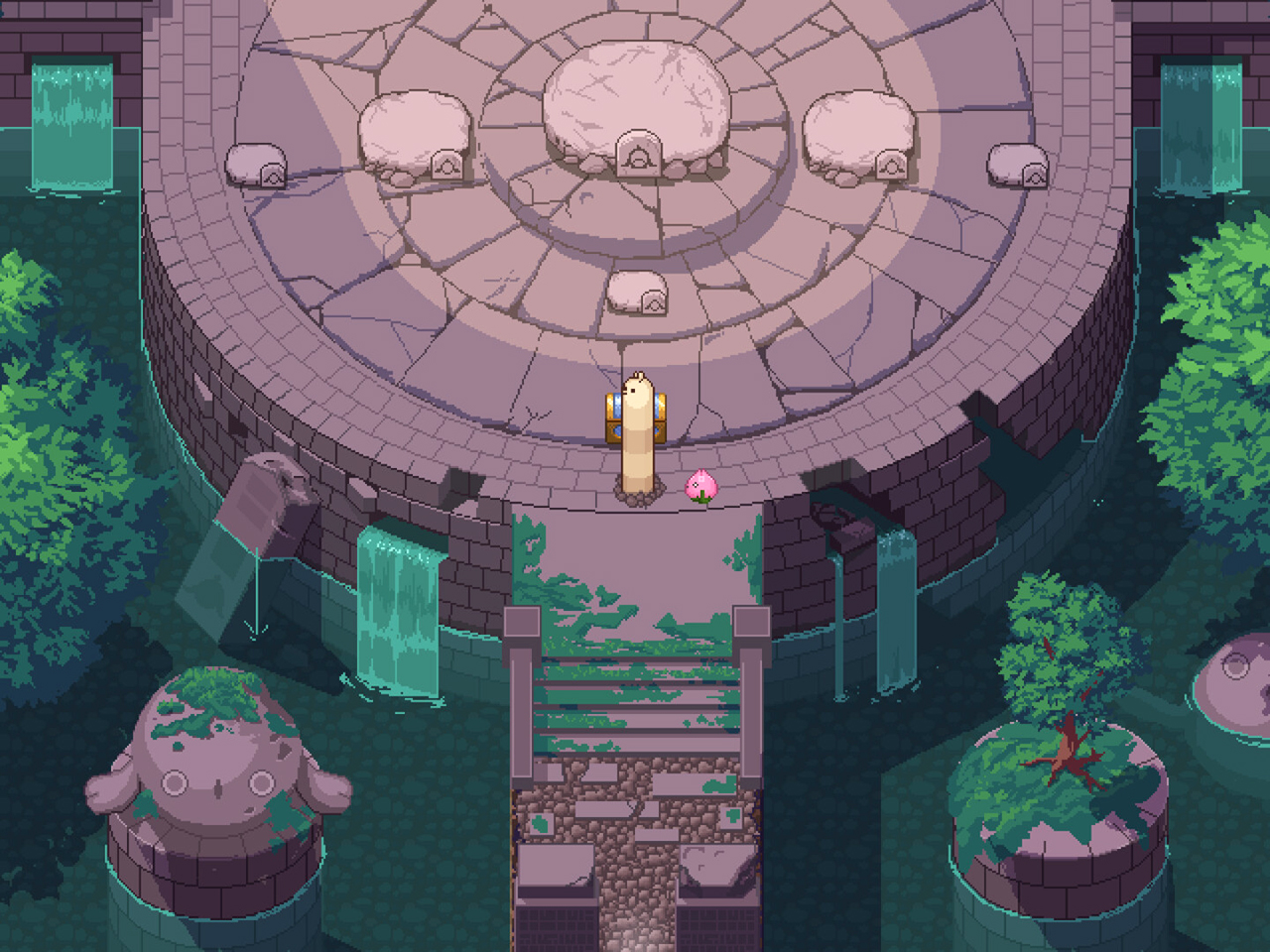

You play as a young boy whose escape pod lands on a deserted island after his spaceship blows up. After the crash, pterodactyls steal the boy’s survival tools and his dog, so it’s up to him to unsheathe his trusty sword and explore the island to get everything back.

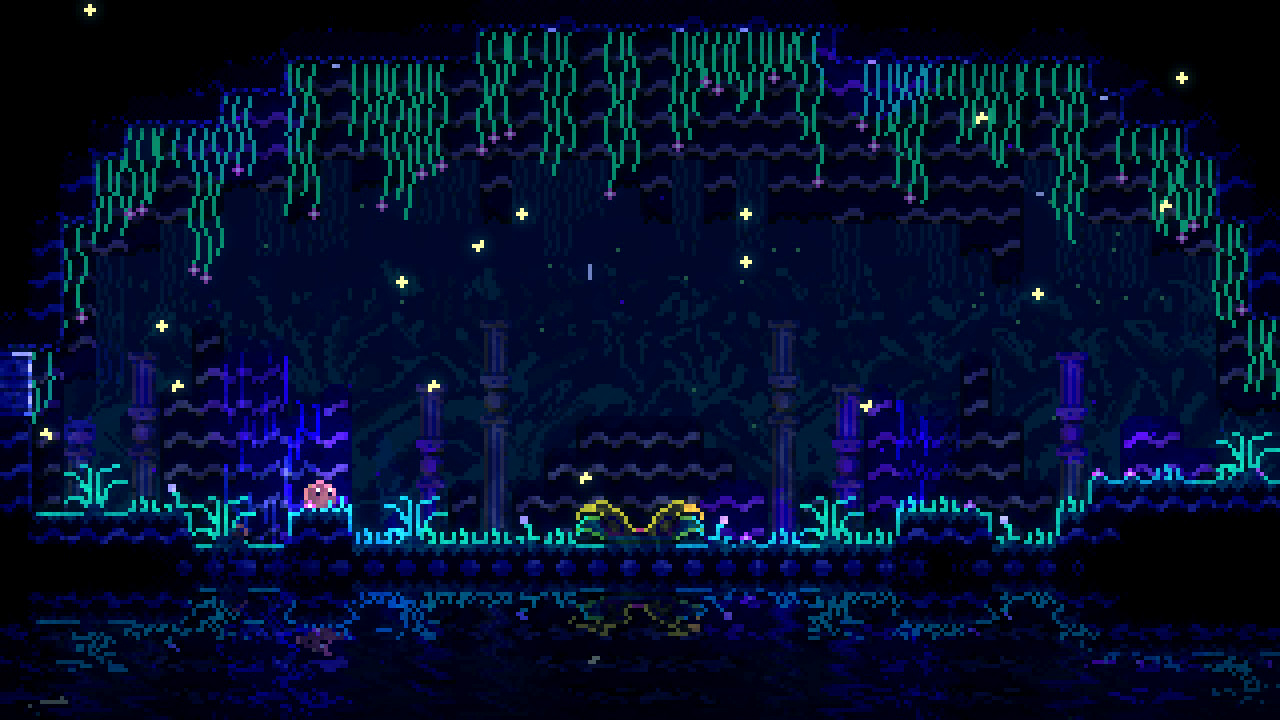

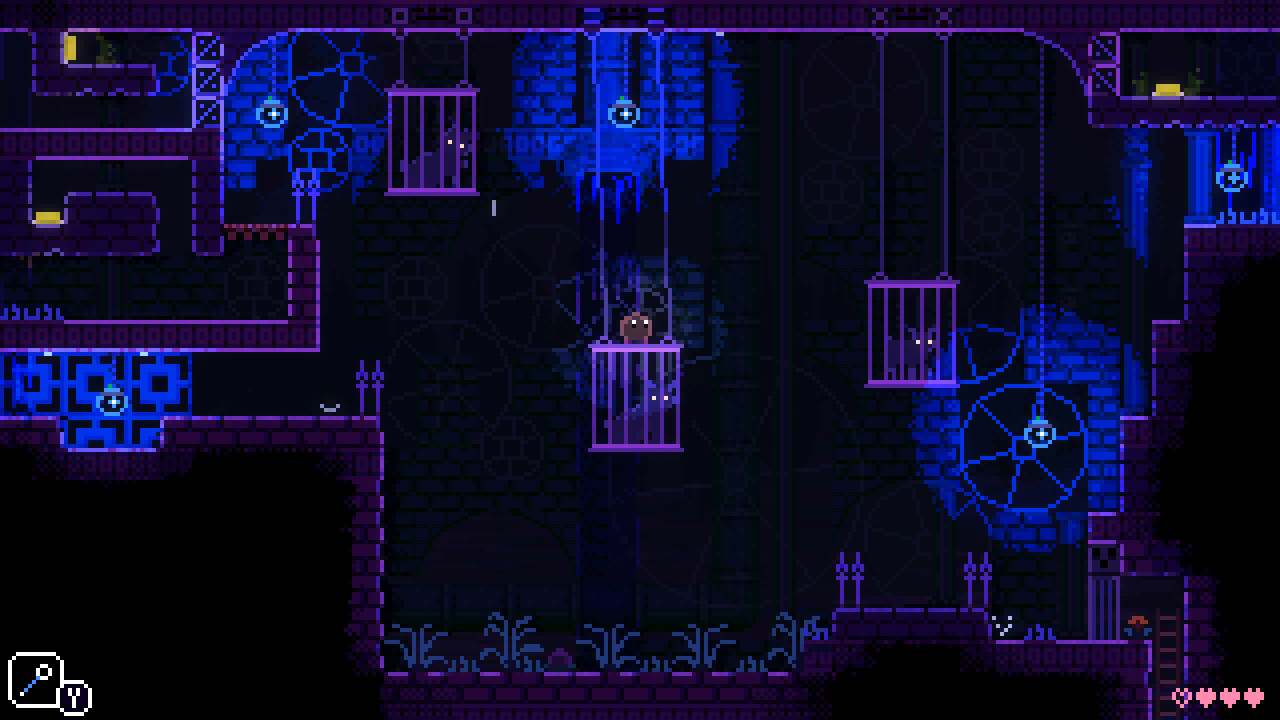

The island is very small, as are each of the three dungeons. There’s no one to talk to, and there are only four types of enemies. The only aspects of the environment you can interact with are two types of rocks, so all of the puzzles involve sokoban-style block pushing. The two tools you find in the first two dungeons are a pickaxe that allows you to break rocks and a hookshot that allows you to latch onto rocks to cross gaps. If you use your tools to backtrack, you can collect three additional hearts to bolster your health.

The overworld map and dungeons are all tight and precise. More than a true imitation of a Zelda game, Castaway’s story campaign seems to be a stage for speedrunning, and there’s a special Speedrun Mode that allows you to see the clock onscreen. I tend not to care about such things, but the Speedrun Mode was a nice excuse to give the game a second playthrough with a bit more challenge.

The music and sound effects of Castaway are forgettable, but the graphics manage to achieve the trick of using modern technology to reproduce what you thought Game Boy Color games looked like when you were younger. The pixel art of the opening and closing animations is gorgeous, and the interstitial illustrations are lovely as well.

Whether this tiny game is worth $8 is debatable, especially if you’re not interested in speedruns or gauntlet survival challenges. I love Link’s Awakening beyond all reason, so I was happy to put down the money to support indie developers while spending an hour in nostalgia heaven. Still, it would have been nice if Castaway had more substance.

If you’re interested in the concept of Castaway but don’t want to spend money on something that feels like it should be a free demo of a larger game, please consider the alternative of Ocean’s Heart, a beautiful and robust Zeldalike game that’s honestly better than most actual Zelda games. If you’re interested, you can check out my review of Ocean’s Heart (here).