While waiting for the Elden Ring DLC to be released, I decided to try my hand at Bloodborne, a gorgeous and atmospheric gothic action adventure game that somehow manages to withhold even more of its story from the player than Elden Ring. I haven’t seen a concise and accurate summary of Bloodborne’s background lore, so I thought I’d take a shot at creating one.

Before anything, it’s important to establish that Bloodborne is loosely based on H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, whose premise is as follows:

The earth is billions of years old, and it has supported multiple civilizations that rose and fell without leaving any trace of themselves behind. One of these civilizations was that of the Great Ones, whose fungal bodies allowed them to benefit from long lives and peaceful societies. The Great Ones developed technology that assisted them in communicating across time and thereby making contact with other civilizations on the planet, including humans. Because the Great Ones are so physically and mentally inhuman, however, these connections are flawed. Sometimes human communication with Great Ones invokes fear, and sometimes it invokes madness that results in aberrant behavior.

In order to facilitate more productive communication, the Great Ones created dream spaces that exist alongside the waking world as separate dimensions. In Homestuck terms, these dimensions are “dream bubbles” that function as self-contained terrariums. In other words, a dream bubble preserves a certain place at a specific moment for the educational benefit of whoever accesses it, kind of like an interactive movie. Time doesn’t flow inside the dream; it repeats. This means that you can trap someone in a dream and use it as a type of prison. In the most famous example, this is what the Great Ones did with Cthulhu, a priest of malevolent cosmic elder gods that would destroy organic life on earth if the planet came to their attention.

Using this mythos as an inspiration, the world of Bloodborne has been shaped by three broad categories of Great Ones.

The first is a group of Great Ones who have tried to communicate with humans. Humans have taken blood from the immortal physical bodies of these creatures. In small doses, the administration of this blood cures illness and prolongs life. In larger doses, the blood induces physical transformation. A coalition of surgeon-scholars called “the Healing Church” has established itself as a religious organization in the city of Yharnam so that they may perform “blood ministration” on the populace, whom they’re using as test subjects in their experiments to bring humans physically and mentally closer to the Great Ones.

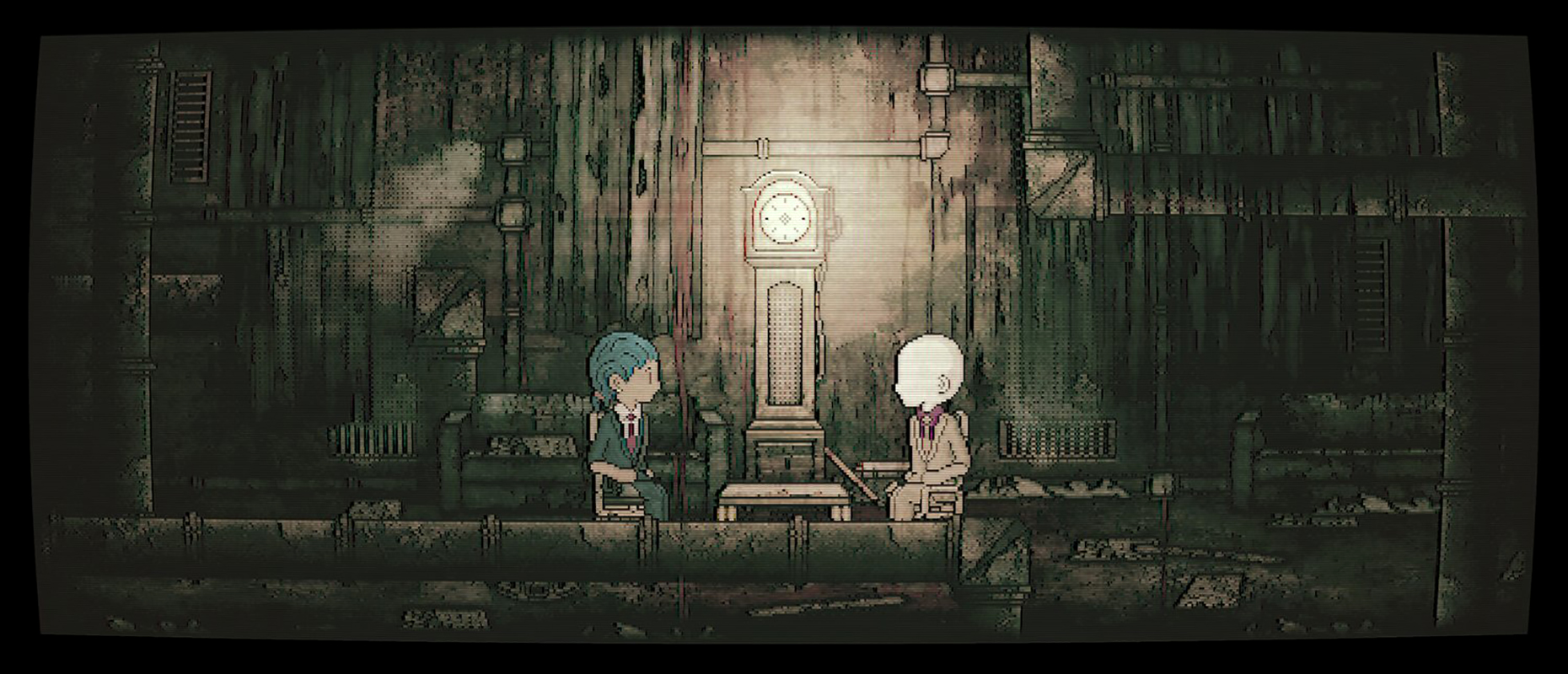

The second group of Great Ones eschews this sort of direct contact and communion between Great Ones and humans. Their motives have little to do with the welfare of human beings, but they’ve nevertheless acted in opposition to whatever is going on in Yharnam. One of these Great Ones, called “the Moon Presence,” has created a dream bubble for the ostensible purpose of training hunters to kill the humans maddened and transformed by blood ministration. This is the “Hunter’s Dream” that serves as the central hub of Bloodborne.

The third faction is a loosely federated group of spiderlike Great Ones called Amygdala, who have created their own set of dream bubbles. Some of these dream bubbles are maintained in cooperation with humans seeking eternal life in a timeless space, while some were created seemingly for the purpose of feeding from the human souls trapped inside them. I believe the version of Yharnam that the player-character navigates exists within a dream bubble created by Amygdala.

Essentially, the world of Bloodborne is a dream inside a connected network of dreams that can be accessed by the player-character as they dream. While the Hunter’s Dream exists as a sanctuary for would-be hunters, the dream that contains Yharnam is something like a training simulation. Your character can only wake from these interconnected dreams (meaning: finish the game) by completing the task they are given as they fall asleep during Bloodborne’s opening cutscene: “Seek Paleblood to transcend the hunt.”

It’s not entirely clear what “Paleblood” refers to, but the game offers two primary interpretations.

The first interpretation is that Paleblood is the blood of the Great Ones that caused the scourge of beasts in Yharnam. Once the player-character understands the full extent of the effects of Paleblood on human physiology and society by witnessing the downfall of Yharnam, they are qualified to become a hunter in the waking world. At the end of Bloodborne, the player-character’s mentor Gherman offers a choice. He can release them from the Hunter’s Dream, or they can best him in combat in order to earn the (highly dubious) honor of replacing him as its warden.

The second interpretation is that the term “Paleblood” refers to the human-adjacent children of the Great Ones, who cannot produce offspring on their own and must rely on human hosts. The conditions for the creation of Paleblood children are unclear, and various factions of the Healing Church have undertaken ghastly experiments on the population of Yharnam in order to pursue this knowledge.

If the player locates and consumes three umbilical cords from unsuccessful Paleblood pregnancies, it’s possible for them to be reborn as a Paleblood squid baby (and future Great One) within the Hunter’s Dream. According to the interpretation suggested by this ending, the Hunter’s Dream was created by the Moon Presence in order to select and nurture potential candidates capable of becoming its child.

The game’s title, Bloodborne, therefore refers to the player-character’s ultimate goal. Either they will be reborn as a fully-fledged Hunter after awakening from the bloody chaos of the Hunter’s Dream, or they will be reborn as a Great One after inheriting the Paleblood of their “parent,” the Moon Presence.

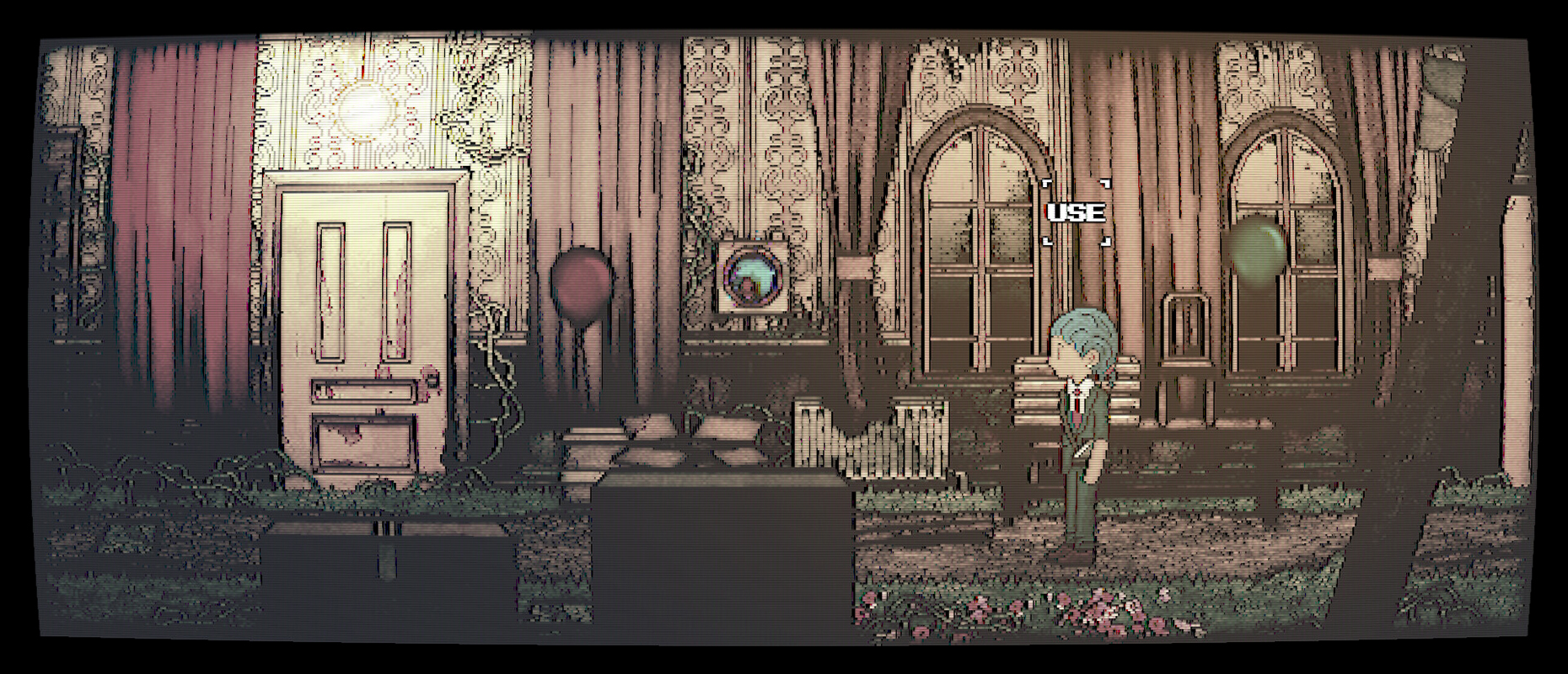

The story of Bloodborne (such as it is) focuses on the player-character’s journey through the city of Yharnam and its outlying areas as they fight the humans who have been transformed into monsters by the blood of Great Ones. The game’s DLC, called “The Old Hunters,” provides additional background information concerning the origins and establishment of the Healing Church through dream encounters with the key figures in its history.

For an excellent synopsis of the story presented by the DLC, I recommend this article: https://www.eurogamer.net/bloodborne-whats-going-on-in-the-old-hunters

For a deeper dive into Bloodborne‘s story presented in well-organized chapters that arrange the aspects of the plot in chronological order, I’d recommend checking out this fan-created wiki, which can be read like a novel: http://soulslore.wikidot.com/bb-plot