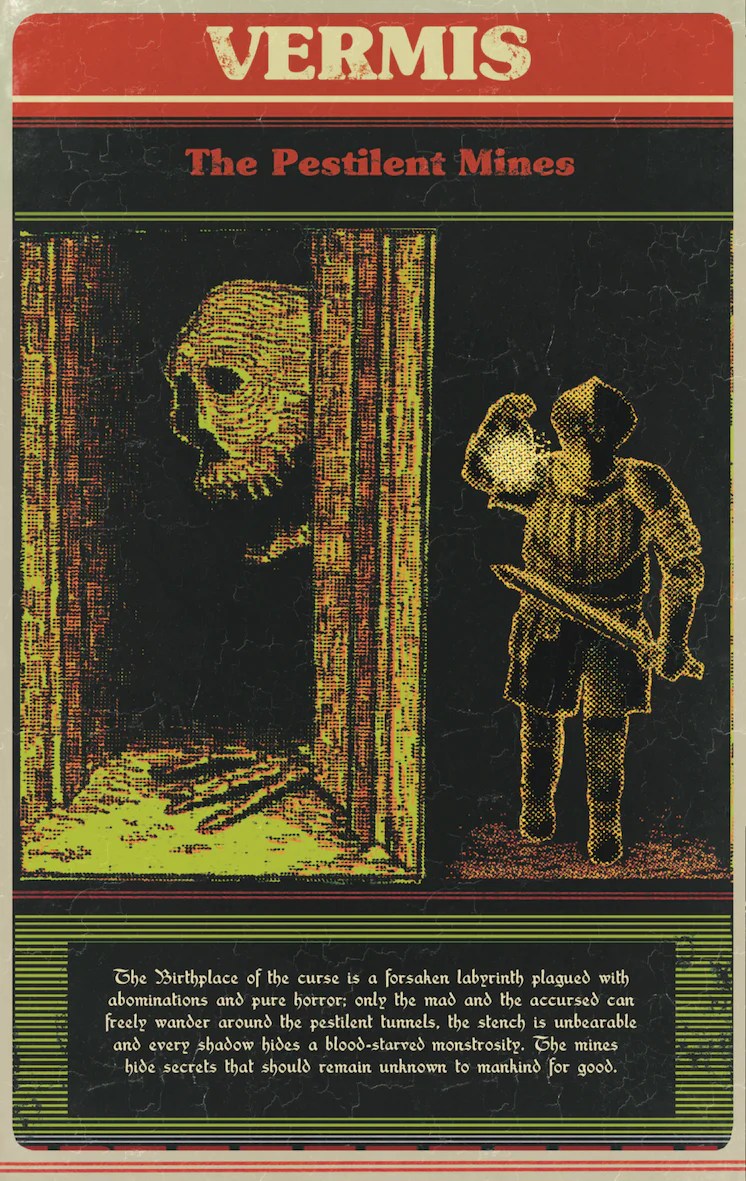

Vermis is an illustrated strategy guide for a dark fantasy game that doesn’t exist. Plastiboo, the author and artist, has taken the concept of “fake strategy guide” and executed it with absolute sincerity and fidelity. Both the writing and the crusty “screenshots” have a pitch-perfect clarity of tone and style that invites immersion.

Before attempting to describe what this book is, perhaps it might be useful to describe what it isn’t. First, Vermis is entirely original. Although the tenor of its world will be familiar to fans of Dark Souls and FromSoft’s earlier King’s Field series of dungeon crawlers, there are no callbacks or veiled references or tongue-in-cheek jokes about how “it’s dangerous to go alone.” Vermis is entirely its own thing.

Second, though Vermis emulates the style of a strategy guide, Plastiboo has an artistic eye for page layout that many guides published during the 1990s did not. In other words, Vermis is easy to read. It also forms a narrative, albeit not in a novelistic sense. Although the text is fragmented, the reader never struggles to move from page to page. This is not House of Leaves.

Third, Vermis is more “dark fantasy” than “horror.” Although there are stylistic elements of the gothic and grotesque, Vermis never attempts to provoke dread, disgust, or anxiety. I wouldn’t call Vermis “understated,” as it features all manner of unsightly monsters, but its tone is quiet and contemplative. Aside from your character’s constant forward progress, there’s not much action.

Vermis is written entirely in a second-person point of view, a stylistic choice that works well in this context. The player-character has no set identity, so the “you” of the story is handled lightly and never becomes overbearing. The second-person narration successfully achieves its intention, which is to draw the reader deeper into a sense of playing the game.

After being introduced to a range of starting classes, you wake into a peaceful area called Deadman’s Garden, whose ferns and mosses are protected by the skeleton of a sleeping giant. You then descend into an isolated crypt, where you loot your first sword from a corpse. You also meet your first NPC, the Lonely Knight.

The Lonely Knight is not hostile, and Vermis reproduces the boxes of dialogue with which he greets you. Although Plastiboo is canny enough to keep the narration of battles to a minimum, the format of Vermis obliquely suggests gameplay. “Despite his imposing appearance,” the text reads, “the Lonely Knight is totally harmless and will not defend himself from any attack.” Underneath this passage, however, is an insert featuring illustrations of the knight’s equipment, which your player presumably receives by killing him.

After navigating through the Isolated Crypt and emerging from its cliffside exit, you then venture into a swamp, a forest, and more crypts and caves, each of which is characterized by its own unique theme.

Along the way, you cross paths with various NPCs (mostly fellow knights) and pick up a collection of items. The text describing these items and encounters alludes to gameplay that’s never made explicit. The decision to leave the more interactive elements of Vermis to the reader’s imagination works in concert with the second-person narration to draw the reader deeper into the ludic simulacrum. For example, in this passage…

Once on the other side of the bridge, you notice how the oppressive flutewood landscape is replaced with clear skies and endless hills full of cedars. The breeze blows gently.

After days surrounded by the unrelenting melody of the flutewoods, the absence of the whistles makes for a heavenly silence interrupted only by the chirping of the birds and the wind blowing through the leaves.

An enormous structure rises at the top of the highest hill, casting a shadow that engulfs the landscape. You make your way to the building as the sun goes down. The contrast with the sky makes it difficult to discern what is inside.

…the mechanical process of crossing this space is merely suggested. Instead, the reader is presented with the more subjective elements of the game.

Having just survived a difficult battle on the aforementioned bridge, your sense of relief is reflected in a green and peaceful landscape. The relative silence has a tangible quality. In contrast to the twisting corridors of underground dungeons, here you can hear birds and feel the wind. The sky is open. Nevertheless, the final labyrinth lies ahead, so onward you must go if you wish to reveal the secrets hidden inside.

In his review of Vermis, “The Guide to a Game That Doesn’t Exist,” Patrick Fiorilli writes, “As a strategy guide — precisely insofar as it is a strategy guide — Vermis makes good on the promise that such volumes once made to their readers: that there is a world beyond these pages waiting to be explored.”

Fiorilli continues, “Vermis also builds the speculative world of its own existence: a world where this bygone form of secondary literature, the strategy guide, never disappeared, never dissolved into the slush of the content economy, but instead flourished as an aesthetic form unto itself.”

Fiorilli’s hints regarding the metafictional resonance of the “speculative world” of Vermis are intriguing. There’s an element of liminality to the book that recalls the famous “Candle Cove” online horror story about a half-remembered children’s cartoon that aired on a public access channel that never existed. Describing the “dreamcore” aesthetic of “liminal” videos such those surrounding the mythology of The Backrooms, digital architecture critic Ario Elami notes, “Responses to such imagery often involve claims that one feels dislocated yet aware of a vaguely familiar aspect.” And indeed, Vermis possesses this exact sense of uncanny belonging to a history that almost was.

Still, I’m far more interested in Vermis’s proximity to the “speculative world” that Fiorilli describes at the beginning of his review as he relates his experience of studying the strategy guide for The Wind Waker before playing the game. I once enjoyed similar experiences of engaging with old video games purely through their strategy guides, and I can attest to the pleasures of constructing an interactive experience through grainy images and their accompanying captions.

Through some unholy miracle, Vermis perfectly captures the spirit of “playing” a game through interaction with a paratextual artifact. At the same time, Vermis discards many elements of an actual strategy guide in order to structure its text and layout to form a satisfying narrative. It’s a delicate balance, and I’m in awe of how Plastiboo manages to pull it off.

I spent a month doing internet deep dives while trying to find more books like Vermis, but everything I saw people recommend – from Fever Knights to Tales from the Loop – didn’t scratch the same itch. Thankfully, Vermis has a “sequel,” Vermis II, which is a fascinating evolution of the formula that engages with the meta while still offering an adventure that stands on its own. In addition, Plastiboo’s publisher, Hollow Press, also offers three similar titles: Age of Rot, Leyre, and Godhusk. They’re all fantastic, albeit slightly edgier and more tonally graphic than Vermis.

Of all the books published by Hollow Press, Vermis remains my favorite. I’d recommend it especially to people who don’t want to play Dark Souls (or King’s Field) but are still curious about the atmosphere and flavor of this genre of games. I’d also offer the book to connoisseurs of experimental fiction who want to feel creatively invigorated by a uniquely stylized way of constructing a world through words. Vermis is really something special, and my gratitude goes out to Michele Nitri for making his dream of Hollow Press a darkly fascinating reality.